click for 360 tour

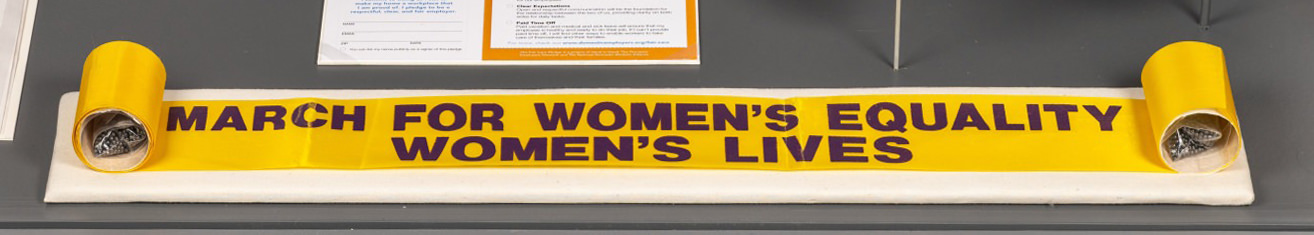

March

for Women's Equality, Women's Lives sash, 1989

Fabric

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

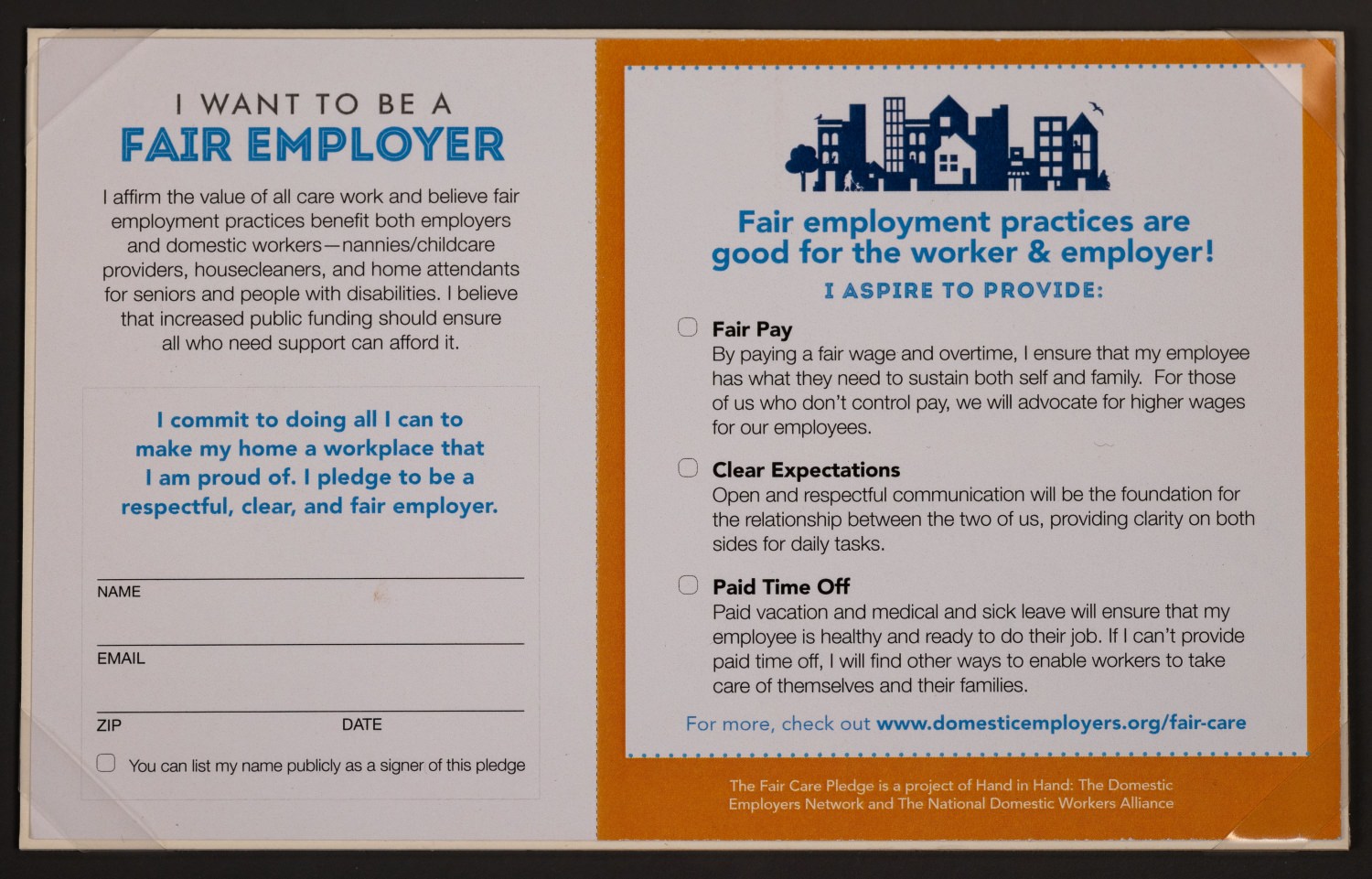

Hand in Hand: The Domestic Employers

Network and the National Domestic Workers Alliance

Fair Care Pledge mailer, 2019

Collection of Anna Danziger Halperin

Based on the

credo that “carework makes all work possible,” domestic work organizing has

been a growing form of women’s collective action, which in recent years

includes marches, legislative lobbying, protests, innovative technologies, and

more. This “Fair Care Pledge” represents a cross-class solidarity-building

project between domestic workers and their employers. Operating much like a

consciousness-raising group of the 1960s, its organizers hope to raise

awareness alongside improving working conditions.

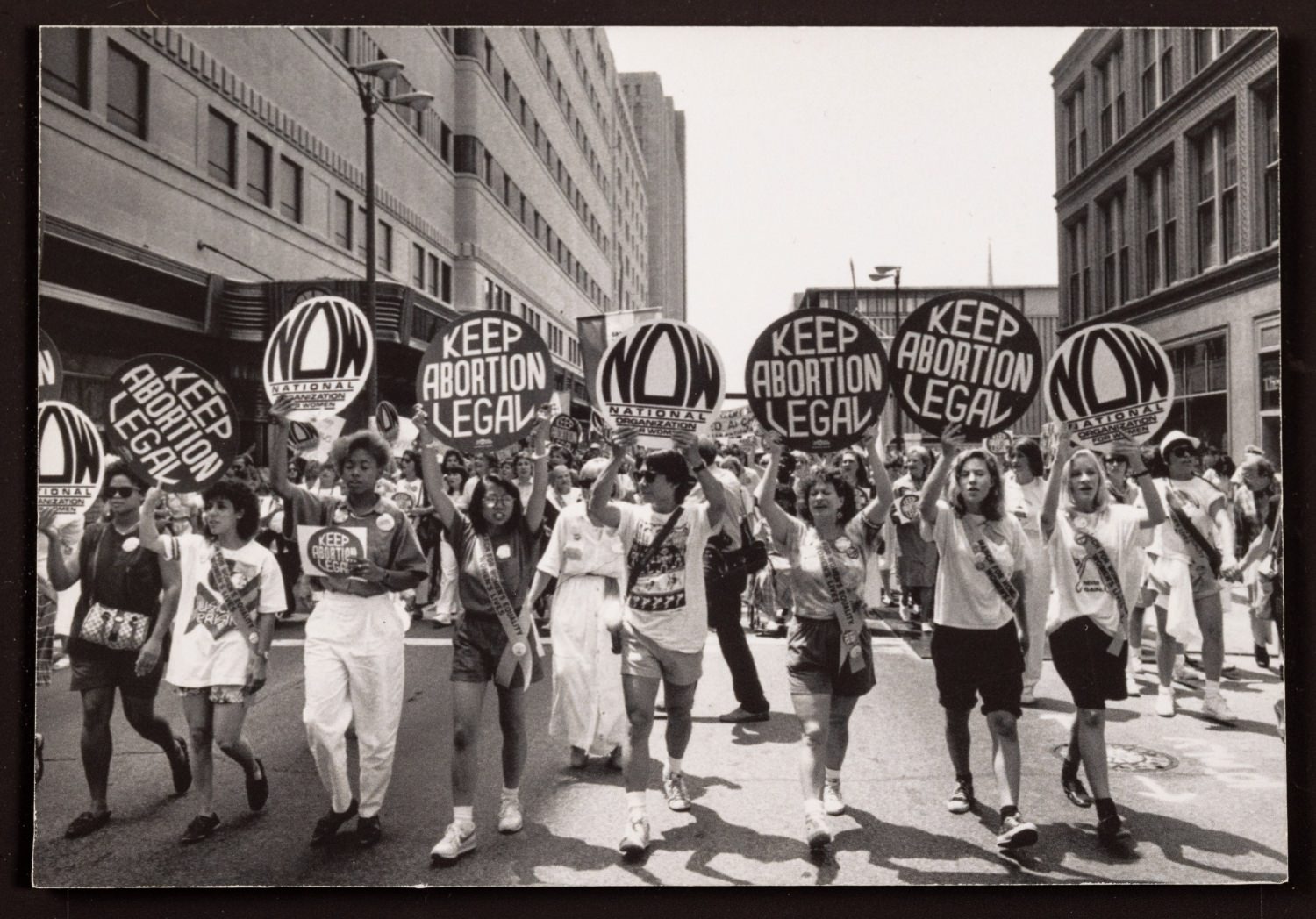

Dorothea

Jacobson-Wenzel

Women walking in NOW

March for Pro-Choice, 1989

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute,

Harvard University

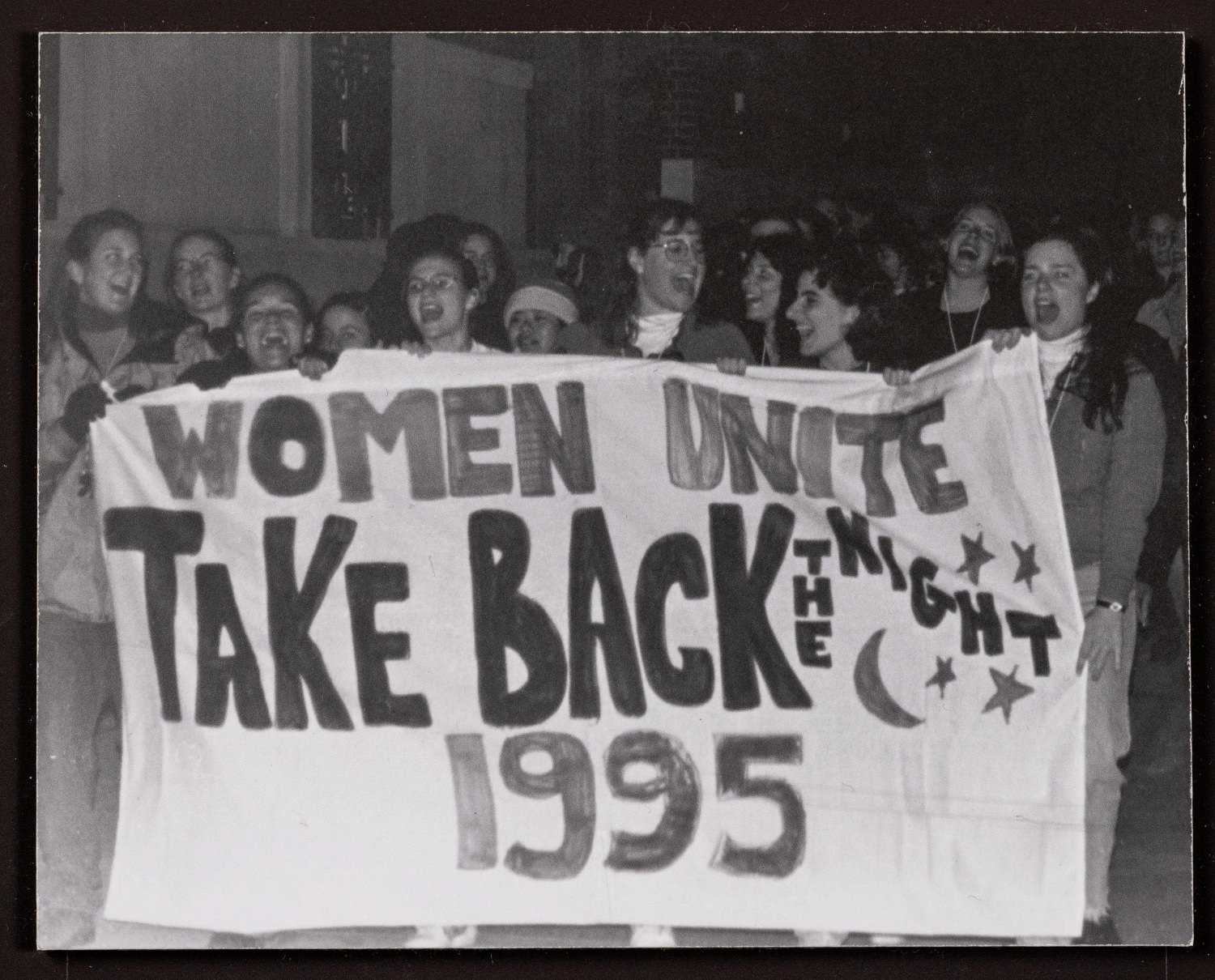

Women Unite, Take Back the Night, 1995

Barnard

Archives and Special Collections

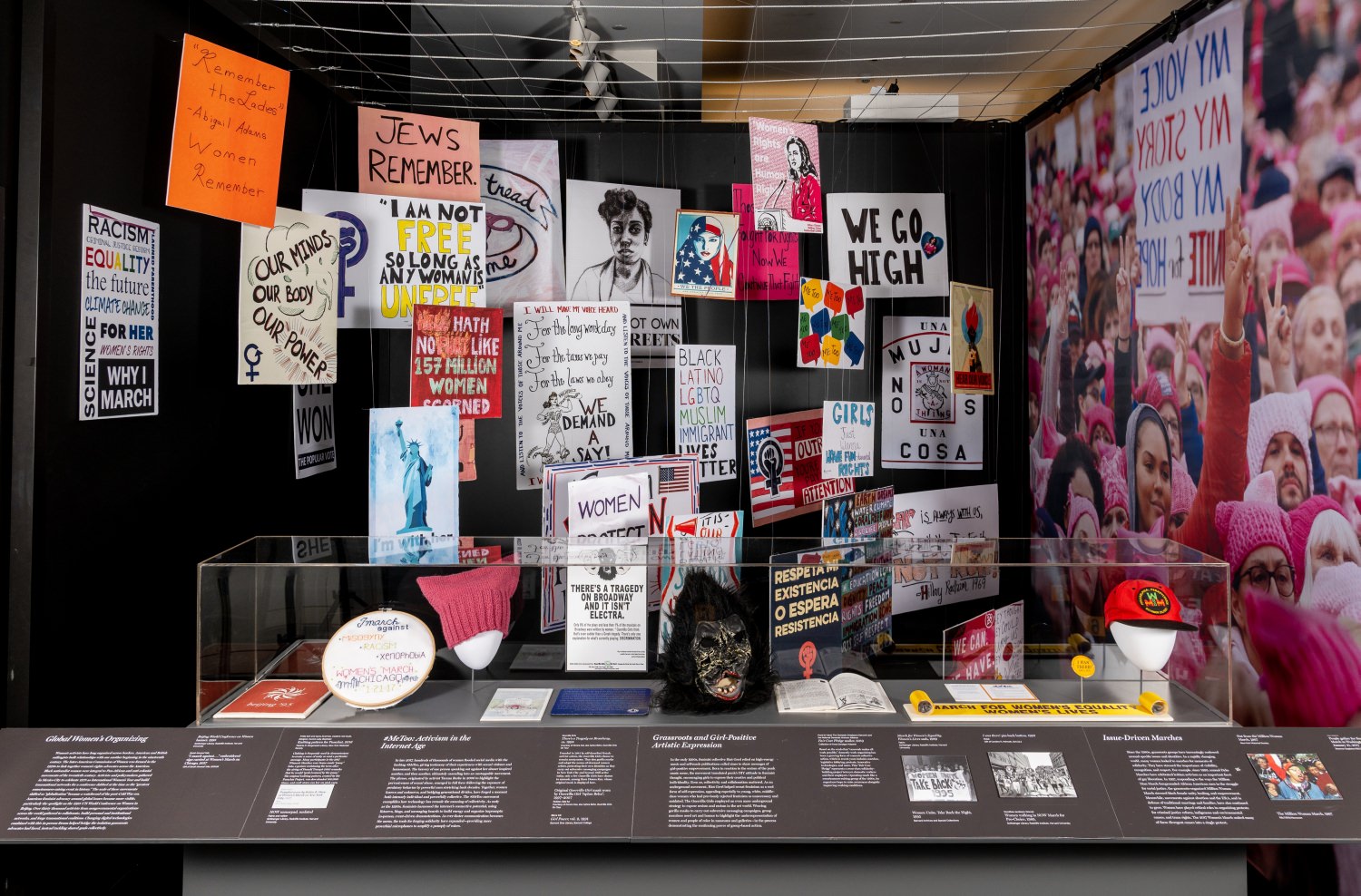

#MeToo:

Activism

in the Internet Age

In late 2017, hundreds of thousands of women flooded social media with the hashtag #MeToo, giving testimony of their experiences with sexual violence and harassment. The bravery of one person speaking out against her abuser inspired another, and then another, ultimately cascading into an unstoppable movement. The phrase, originated by activist Tarana Burke in 2006 to highlight the pervasiveness of sexual abuse, emerged in full force following the exposure of predatory behavior by powerful men stretching back decades. Together, women known and unknown, and bridging generational divides, have forged a moment both intensely individual and powerfully collective. The #MeToo movement exemplifies how technology has remade the meaning of collectivity. As early as the 1990s, feminists harnessed the internet’s connective potential, using listservs, blogs, and messaging boards to build energy and organize impromptu in-person, event-driven demonstrations. As ever-faster communication becomes the norm, the tools for forging solidarity have expanded—providing more proverbial microphones to amplify a panoply of voices.