click for 360 tour

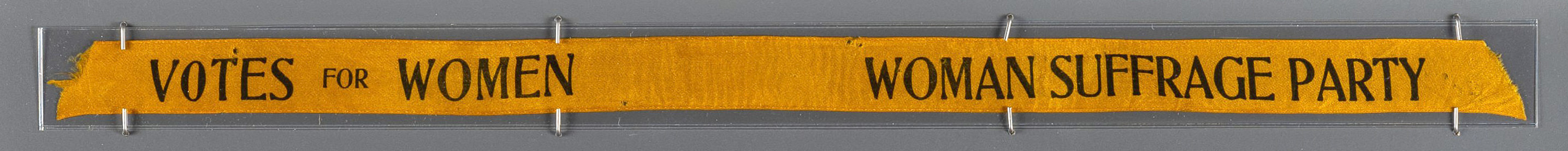

Different

colors signaled different philosophies. Green and purple were associated with

the militant British suffrage movement.

After the failed 1915 referendum in New

York, some groups chose yellow to avoid radical connotations.

Anti-suffrage

groups chose entirely different color schemes.

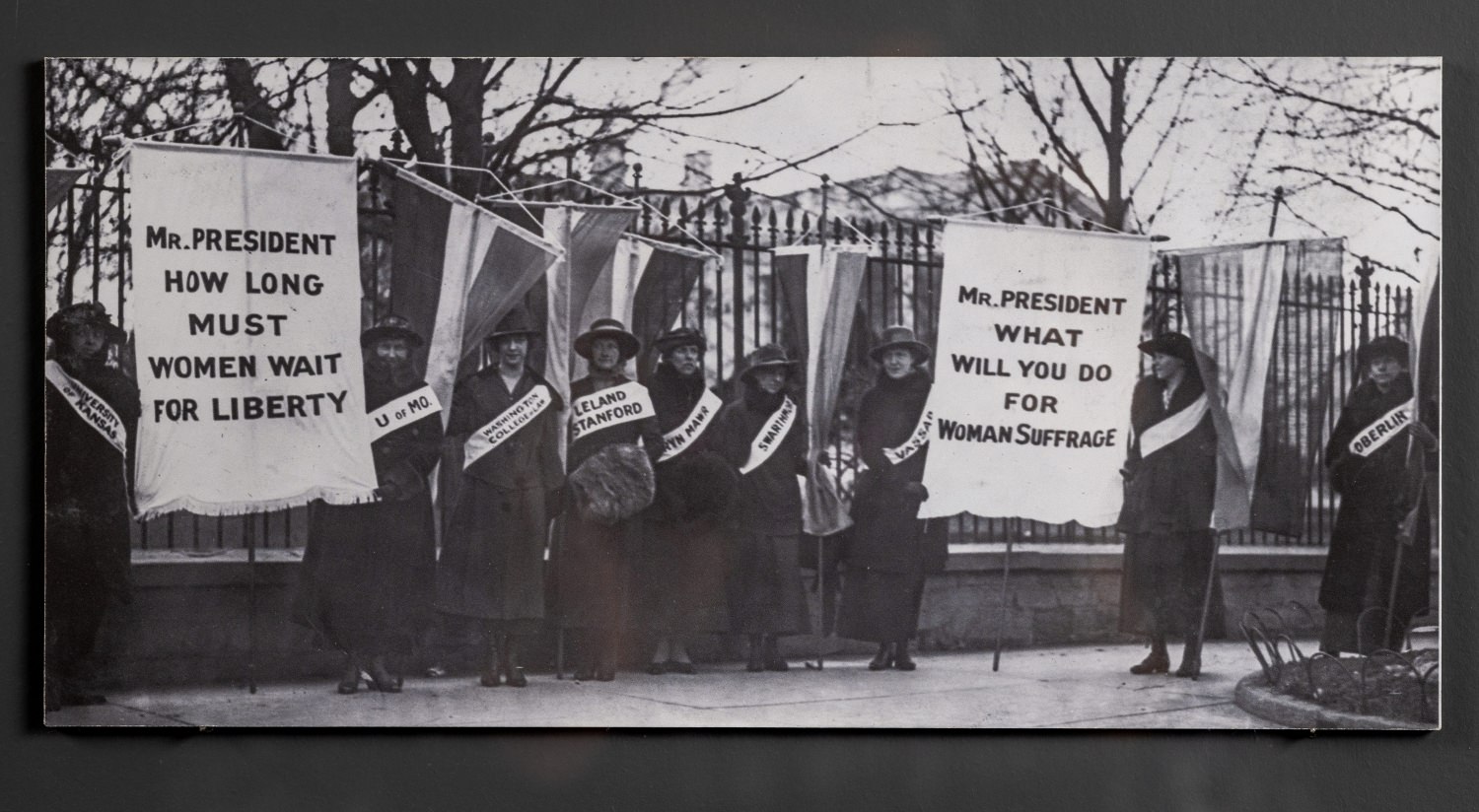

National Women’s Party Pickets, 1917

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs

Division, Washington D.C.

Alice

Paul organized pickets outside the White House. The banners became increasingly

provocative, and she and many of her “Silent Sentinels” served time in a

workhouse for disturbing the peace.

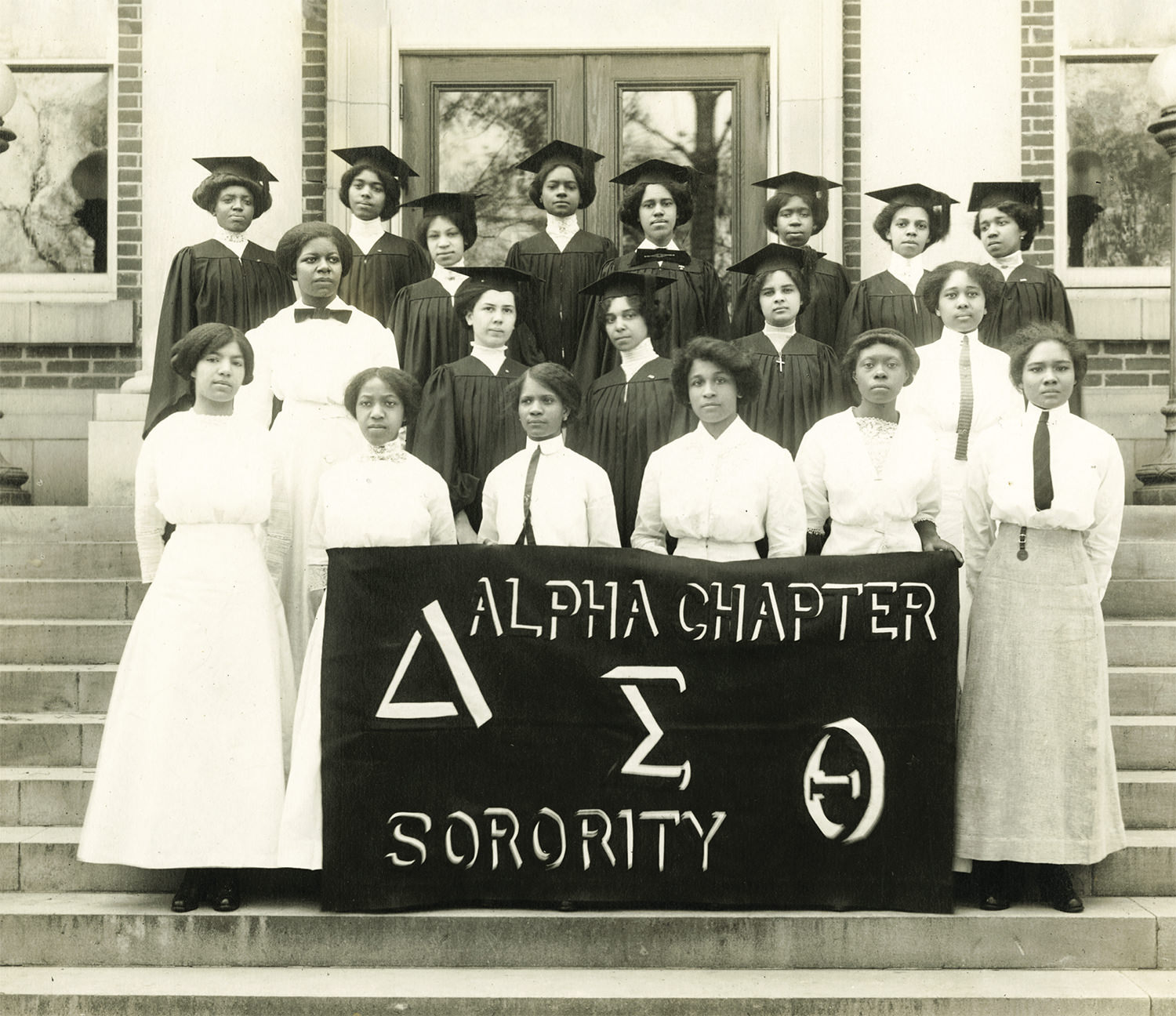

Howard University Delta Sigma Theta founders, 1913

Courtesy of the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and

Howard University

Fearing

the objections of Southern suffragists, Alice Paul first discouraged Black

women from participating in the March 1913 parade in Washington, DC, then

agreed to segregate them at the back of the procession. The young founders of

Delta Sigma Theta marched, as did many well-known Black suffragists including

Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells.

A copy of this photograph is displayed

at the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Incorporated National Headquarters located at 1707 New

Hampshire Avenue, Northwest, Washington, DC 20009.

Front Row: Winona Cargile Alexander, Madree Penn White, Wertie

Blackwell Weaver, Vashti Turley Murphy, Ethel Cuff Black, Fredericka Chase

Dodd

Middle Row:

Pauline Orberdorfer Minor, Edna Brown Coleman, Edith

Mott Young, Marguerite Young Alexander, Naomi Sewell Richardson

Last

Row: Myra Davis Hemmings, Mamie Reddy Rose, Bertha Pitts Campbell, Florence

Letcher Toms, Olive Jones, Jessie McGwire Dent, Jimmie Bugg Middleton, Ethel

Carr Watson Not Pictured: Eliza Pearl Shippen, Osceola Macarthy Adams, Zephyr

Chisom Carter

Amalgamated Clothing Workers on Strike, Chicago, 1915

Jacob Rader Marcus Center for the

American Jewish Archives

Working women boldly asserted their desire for the

vote. Broadsides proclaimed “every thinking working woman . . . wants the power

the ballot will give her and her fellow workers,” urging workers to attend

meetings and parades “to show the gentlemen we have arrived.”

Headquarters

for Colored Women Voters,

attributed as Georgia, ca. 1920

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg

Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Black

voters fought efforts to keep them from the polls.

The NAACP spoke before

Congress on election-related violence, and these women formed a voters’ group

despite widespread disenfranchisement.

Sievers Studio. Missouri League of Women Voters, 1920. Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis

Equal Rights Envoys of the National

Woman’s Party, 1927

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division,

Washington D.C.

The National

Woman’s Party held that the vote alone did not guarantee equal access to democracy,

and proposed

the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923 to ensure equality and prohibit

discrimination according to sex.