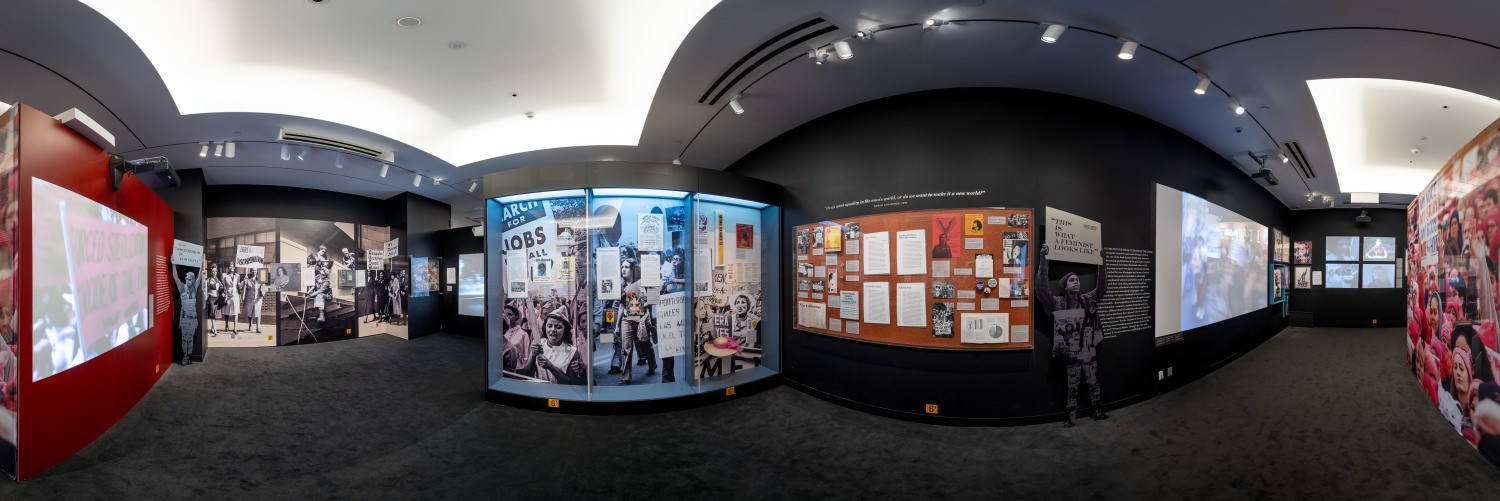

click for 360 tour

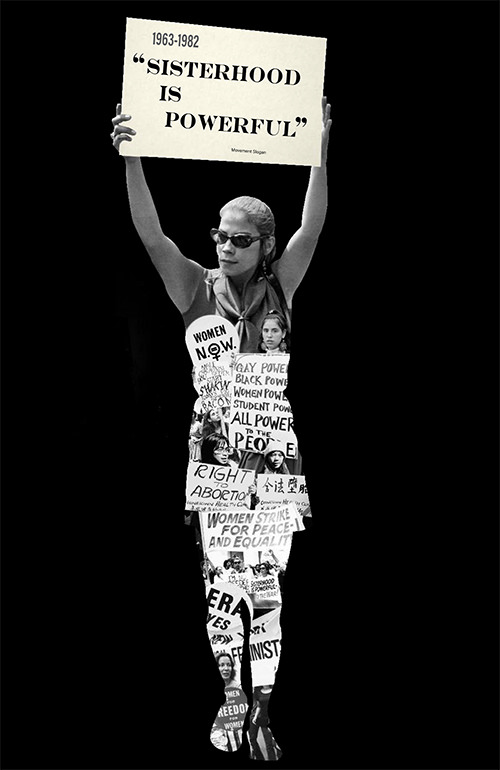

“Sisterhood is Powerful”

–Movement Slogan

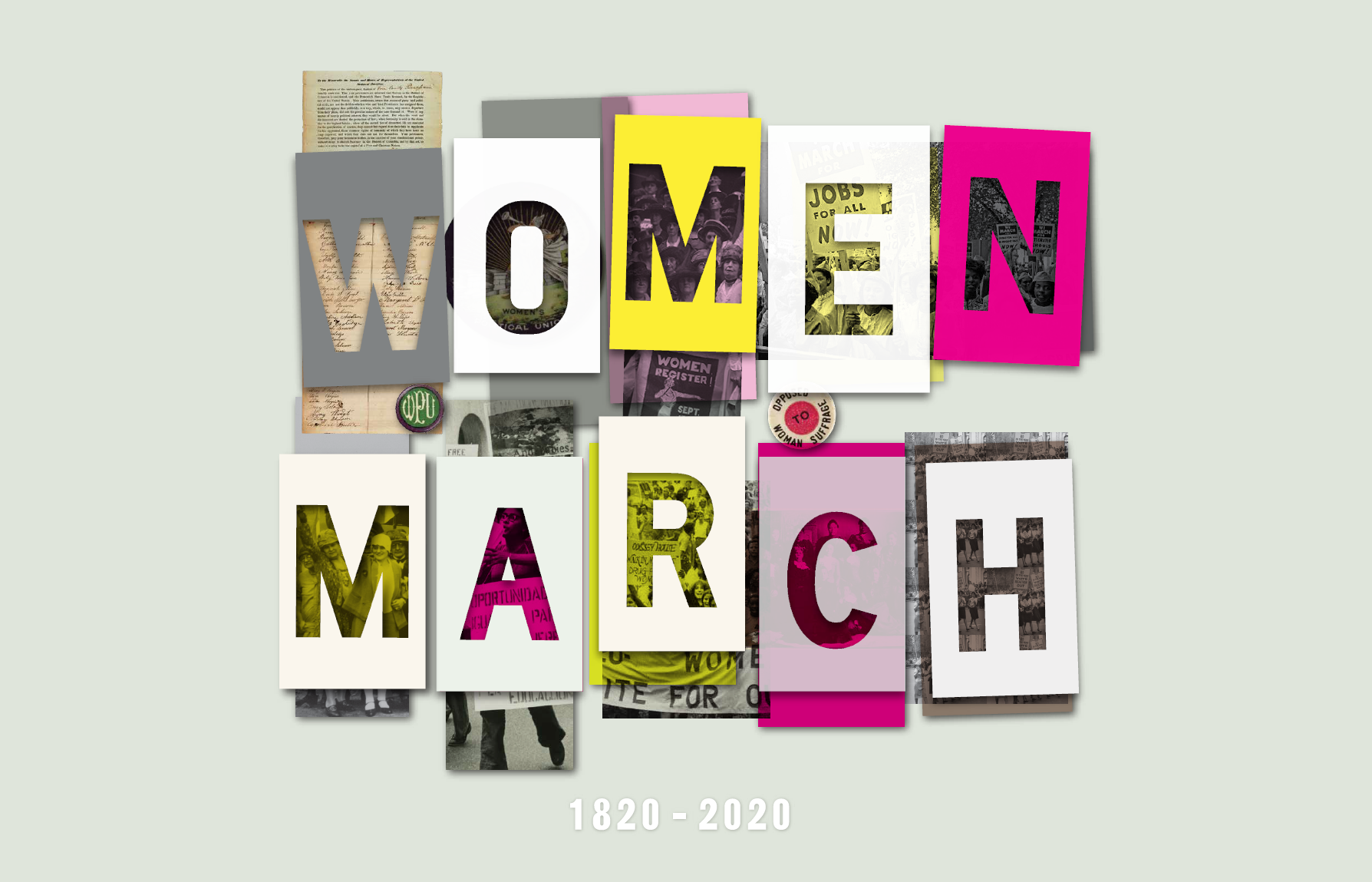

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a mass movement for women’s liberation exploded into national consciousness. Although rooted in earlier feminist thinking and advocacy, it was propelled by new calls for racial and economic justice and sexual liberation that awakened women to the boundaries of their citizenship. A diverse array of women engaged in evolving justice actions, as the Civil Rights movement spawned Black Power, opposition to the Vietnam War intensified—especially among college students—and activists interrogated the links between racism, capitalism, imperialism, and war. In response to the gendered division of labor and their sidelined contributions in these movements, women organized independently as women. Their differences were both a strength and a source of tension. Associations such as the National Organization for Women, grass-roots “consciousness raising” discussions, and radical alliances used a vast arsenal of tactics to change women’s lives across myriad interrelated issues at the local, national, and global levels. Soon, “feminism” would become a household word.

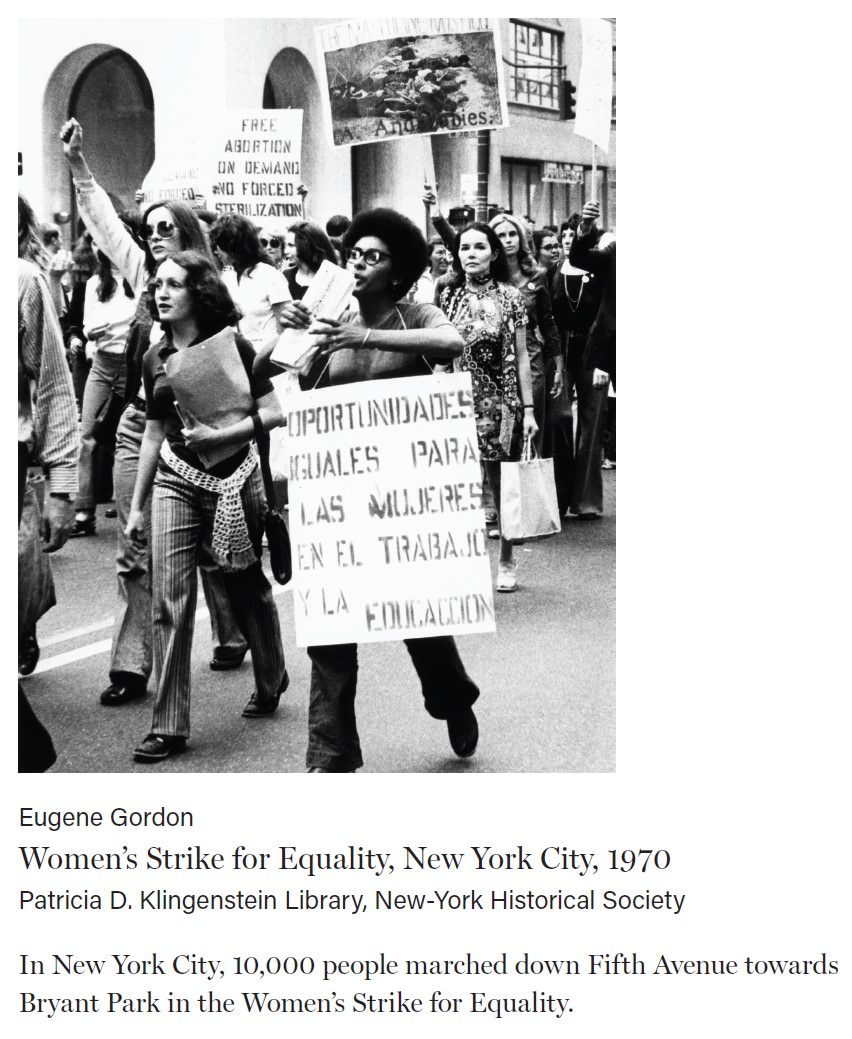

Strike for Women’s Equality, New York, 1970

Demonstration against Forced Sterilization, ca. 1970

Women of the Young Lords, New York, ca. 1970

Mary Dore’s 2014 documentary She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry chronicles the complexities of the

Women’s Liberation Movement. These clips demonstrate a few of the many issues faced by feminists in

the 1970s. Music Box Films

Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965. F.I.L.M. Archive

At the Polls and On the Ticket

For African American women living in the US South, the promise of the 19th Amendment was fulfilled almost a half-century after its ratification. Incidents of racial brutality along with renewed civil rights activity, such as the Mississippi Freedom Summer voter registration campaign, helped bring national attention to widespread voter discrimination and violence occurring in the South. The 1965 Voting Rights Act, which was specifically named an “act to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution,” outlawed poll taxes, prohibited literacy tests, and allowed Southern Black women, with federal assistance, to freely participate in the voting process. Across the country, women harnessed the skills they had honed in civil rights and women’s organizations to run for office. Fannie Lou Hamer, a leader in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, made bids for seats in the statehouse and Congress, while her colleague Unita Blackwell became the first black woman mayor in the state. Patsy Takemoto Mink, an attorney and political activist from Hawaii, and Shirley Chisholm, a Brooklyn educator and NOW co-founder, had historic campaign victories for seats in Congress. Chisholm also sought the US presidency.

Bob Adelman

Young African American women at the March on Washington,

1963

©Bob Adelman Estate

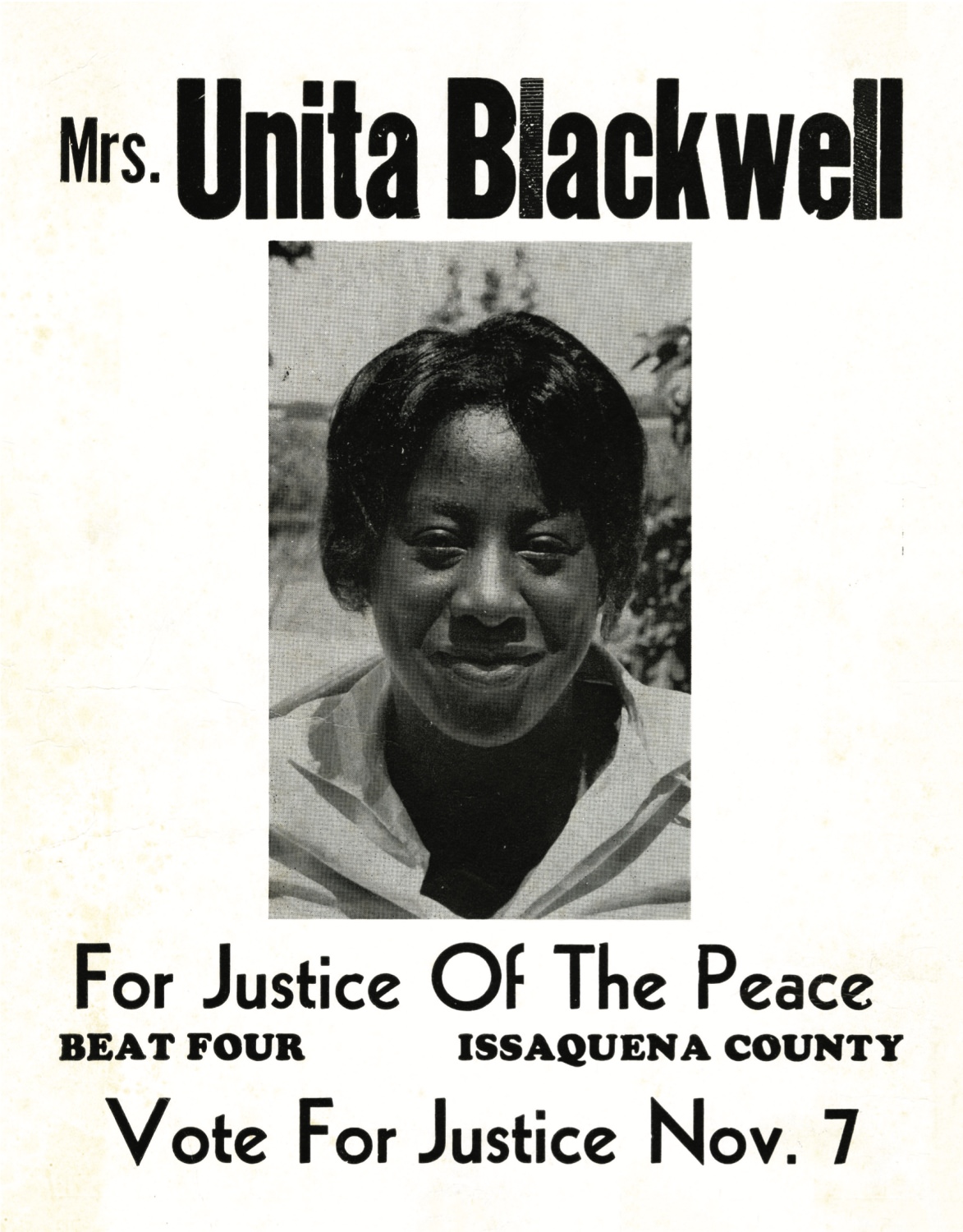

Mrs.

Unita Blackwell for Justice of the Peace campaign poster, 1971

Collection

of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

In 1976, Unita Blackwell became the mayor of

Mayerville, Mississippi, in a county where no Black person registered to vote

prior to the civil rights movement. Her ascension to politics emerged from her

leadership in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. She won a

MacArthur Genius Award in 1992 for her work in civil rights and rural community

organizing.

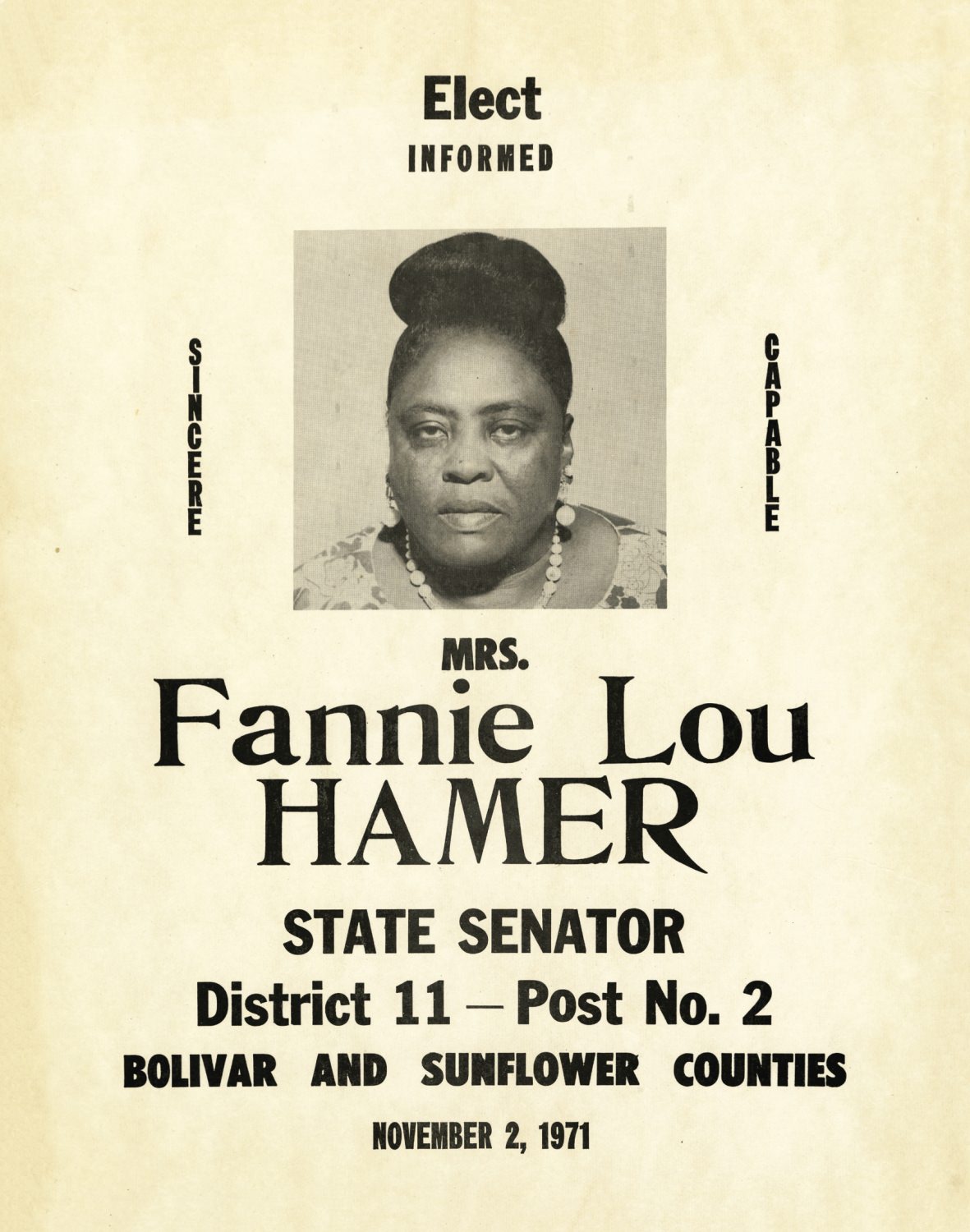

Elect

Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, District 11 State Senate campaign

poster,1971

Collection

of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Fannie

Lou Hamer was a sharecropper in Ruleville, Mississippi, who joined the civil

rights movement in 1962 as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee. After her unsuccessful Congressional run in 1964, Hamer

continued her organizing work with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party,

the Freedom Farm Cooperative, and Head Start.

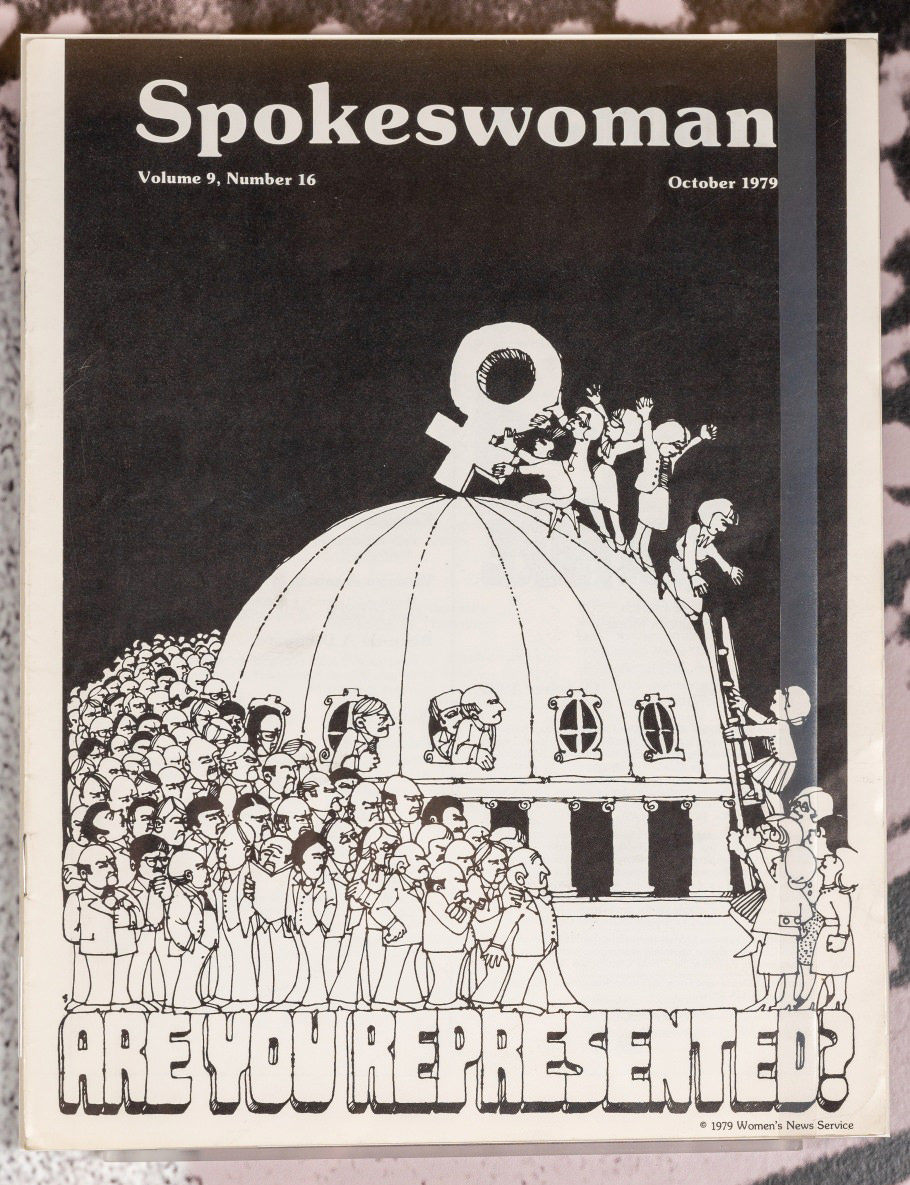

Spokeswoman magazine, October

1979

New-York

Historical Society, Courtesy of Alice Kessler-Harris

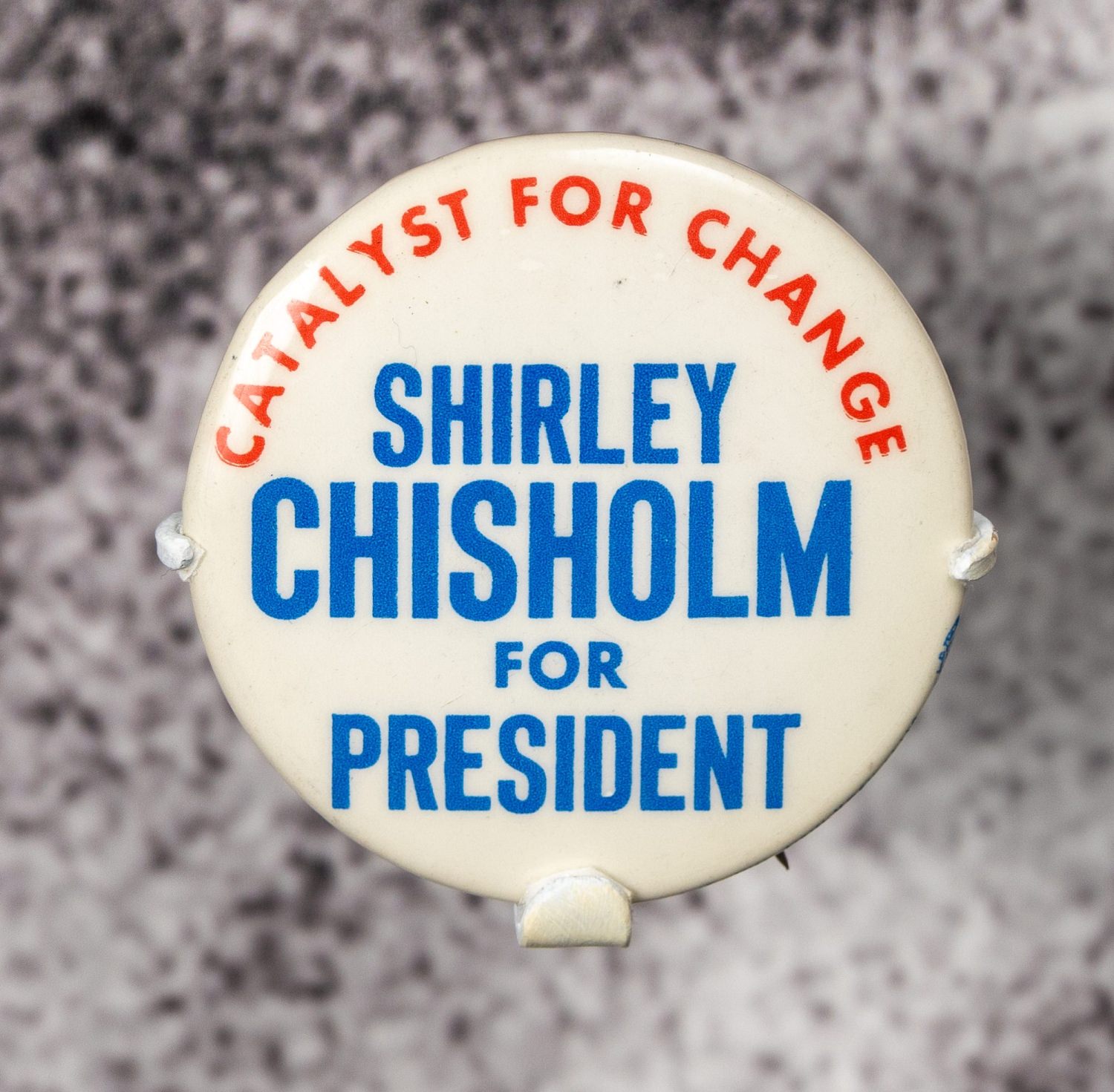

Shirley

Chisholm for President pin-back button,1972

Metal

Gift

of Patricia Falk, 2002.30.7

“The Personal is

Political”

–Movement

Slogan

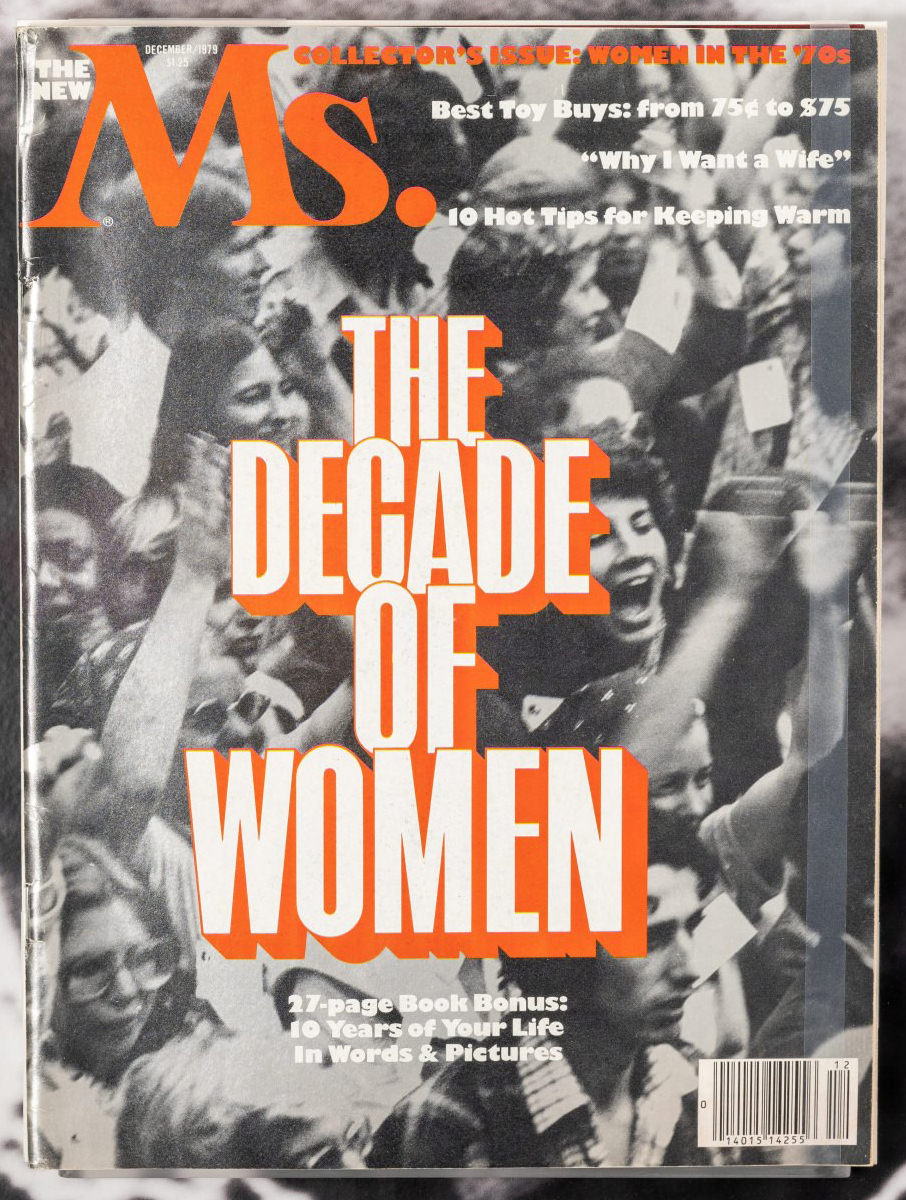

The women’s liberation movement was fueled by the simultaneous civil rights and anti-war protest campaigns, as well as legal and legislative innovations that made sex discrimination actionable. Participants also turned to consciousness-raising as a new strategy for political change. In sharing their experiences, many women realized for the first time that their individual struggles were influenced by institutional, systemic, and political forces. They labelled the confluence of these forces “patriarchy” to indicate the male-dominated society that excluded women from political and social power. Books like Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) and Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics (1970) climbed the bestseller lists. A network of publications, notably Ms. magazine, helped bring feminist ideas before a wide audience. Personal analyses and testimonies—from letters to the editor to published autobiographies—helped women transform individual feelings of shame, isolation, and discontent into a collective desire for widespread change. It propelled them to the streets in marches like the Women’s Strike for Equality.

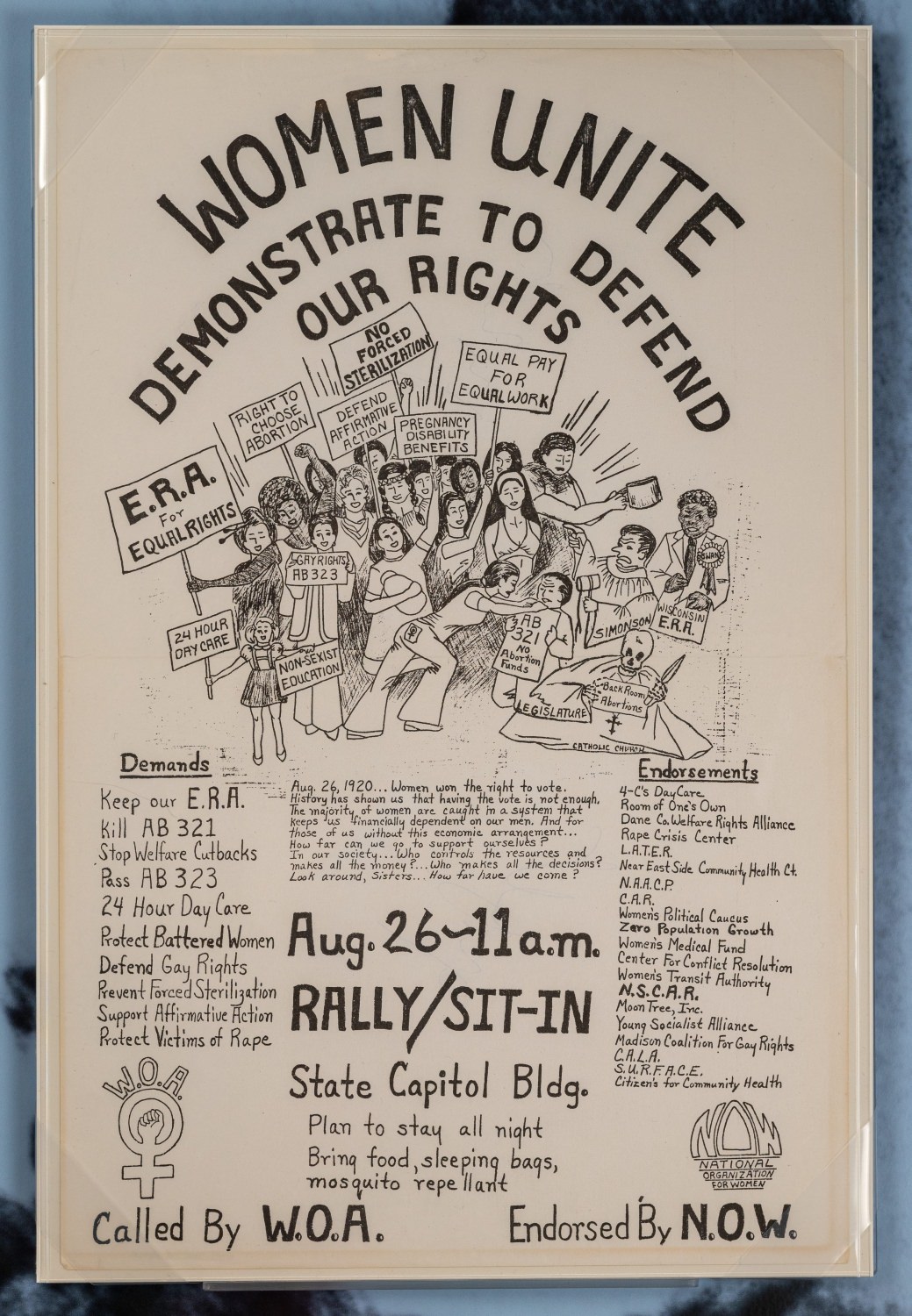

National

Organization for Women

Women

Unite, Demonstrate to Defend Our Rights, 1970

The

Dobkin Family Collection of Feminism

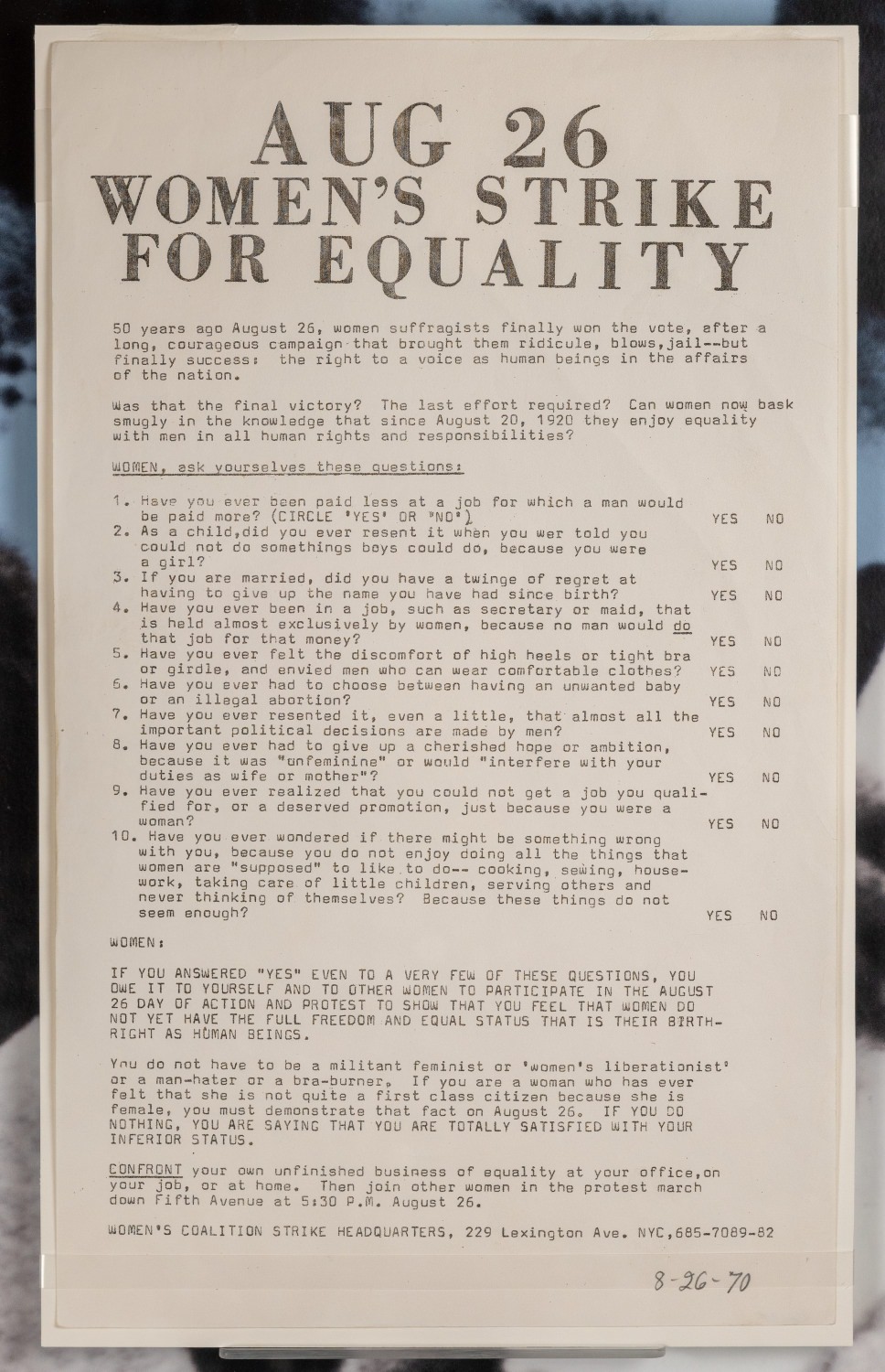

Women’s

Coalition Strike Headquarters

August

26: Women’s Strike for Equality broadside, 1970

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

These posters called upon women to participate in

marches that took place across the nation as part of the Women’s Strike for

Equality on August 26, 1970. The strike marked the 50th anniversary of the

passing of the 19th Amendment and issued new demands for women’s equality,

including equal work opportunity, free childcare, and abortion on demand.

Ms. magazine, December 1979

New-York

Historical Society, Courtesy of Alice Kessler-Harris

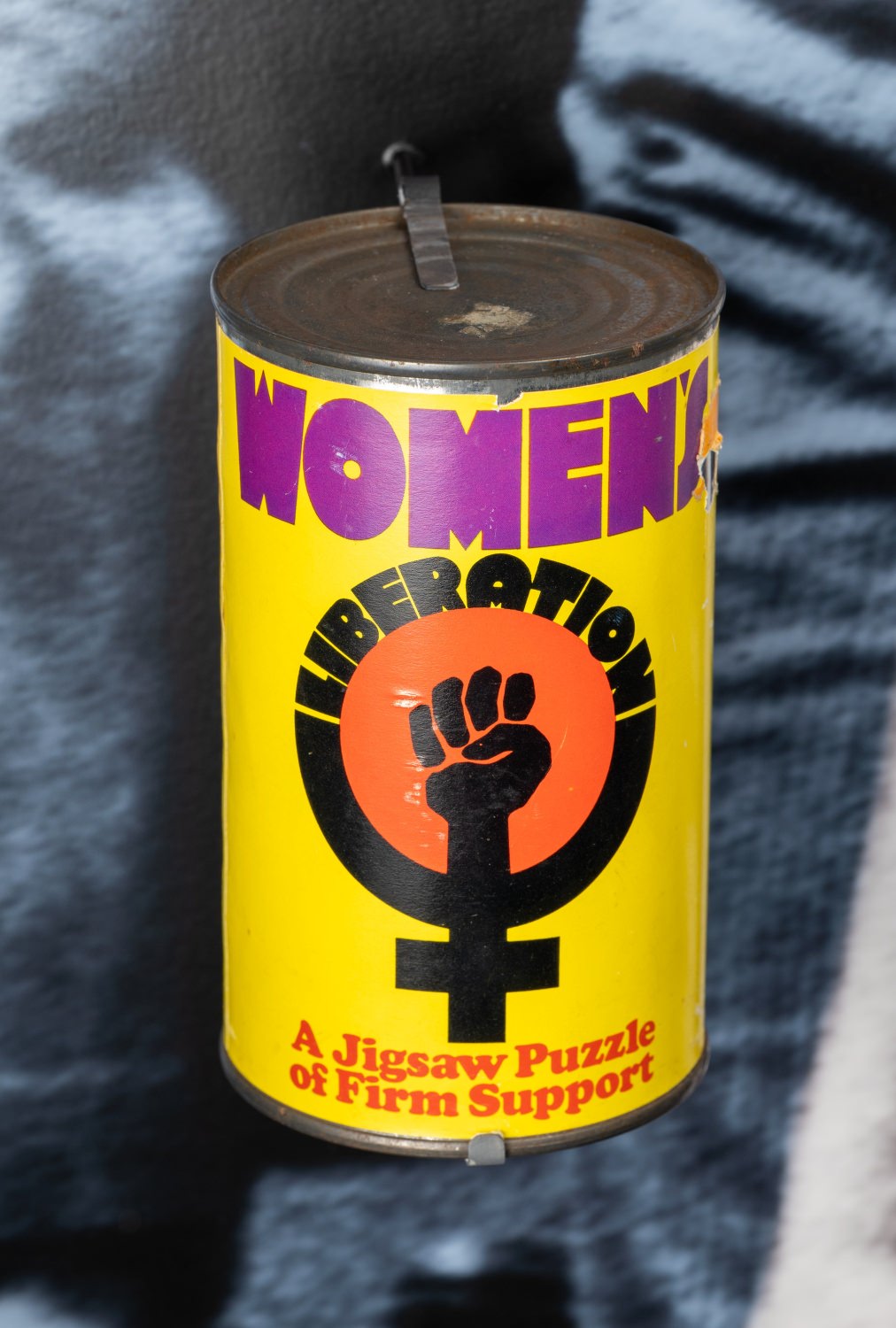

National

Organization for Women

Jigsaw puzzle sold during Women’s Strike

for Equality, August 1970

Metal

and paper

Gift

of Beth M. Eddey, 2014.18.2

Feminist organizations, similarly to their suffrage

predecessors, created items like this jigsaw puzzle bearing the women’s

liberation emblem, and sold them for the dual purposes of fundraising and

spreading their message.

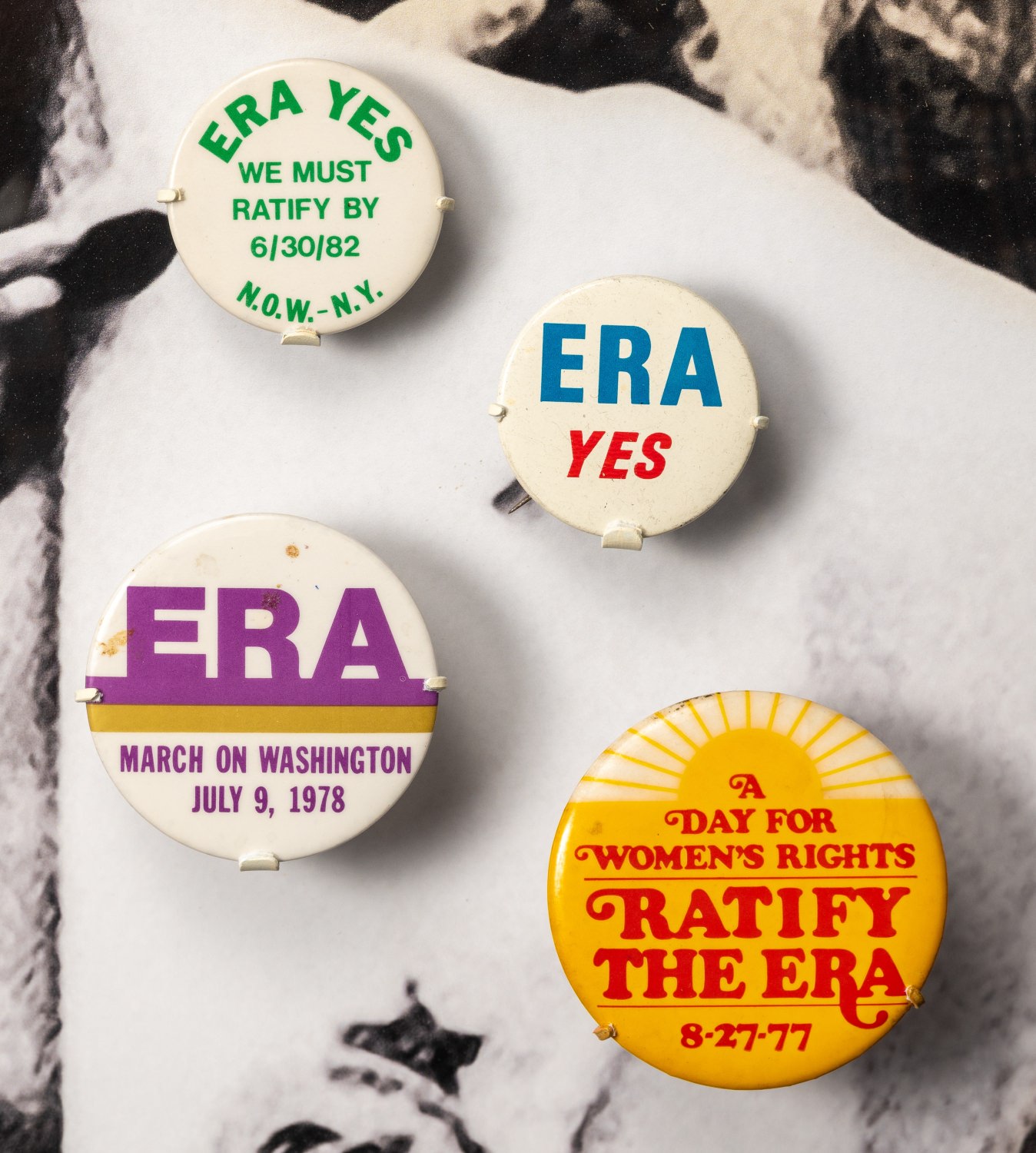

The Equal Rights Amendment

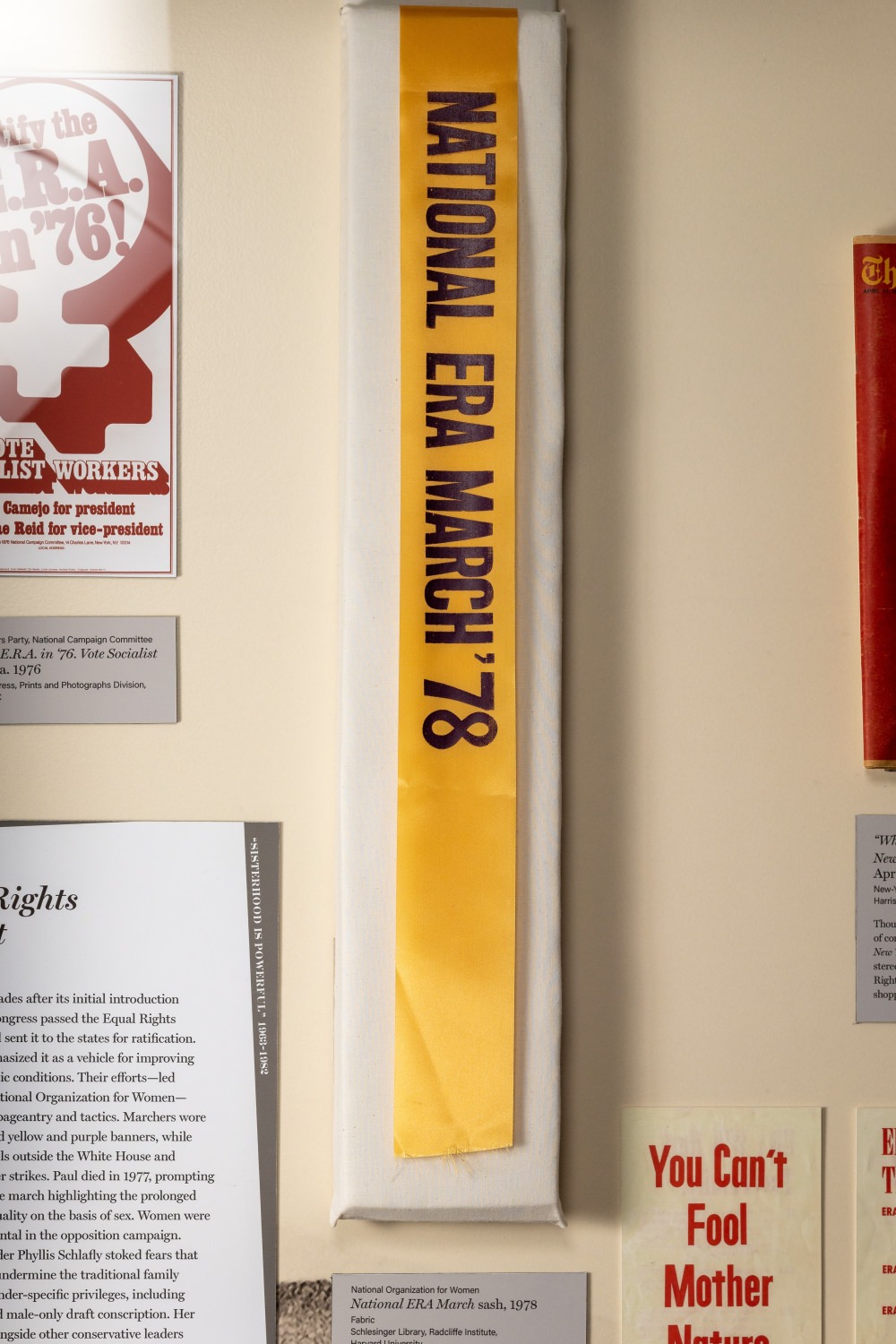

In 1972, five decades after its initial introduction by Alice Paul, Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment and sent it to the states for ratification. Supporters emphasized it as a vehicle for improving women’s economic conditions. Their efforts—led largely by the National Organization for Women—evoked suffrage pageantry and tactics. Marchers wore white and carried yellow and purple banners, while radicals held vigils outside the White House and conducted hunger strikes. Paul died in 1977, prompting a commemorative march highlighting the prolonged fight for legal equality on the basis of sex. Women were equally instrumental in the opposition campaign. Conservative leader Phyllis Schlafly stoked fears that the ERA would undermine the traditional family and eliminate gender-specific privileges, including child support and male-only draft conscription. Her Eagle Forum, alongside other conservative leaders and groups, mobilized a mass grassroots network to marches, letter-writing campaigns, and conferences. They also protested proposals for public child care, the legalization of abortion, and school integration. In 1982, the ERA fell three states short of the 38 needed for ratification. A major plank of the feminist platform splintered, prompting a reevaluation not only of future activism, but the definition of feminism itself.

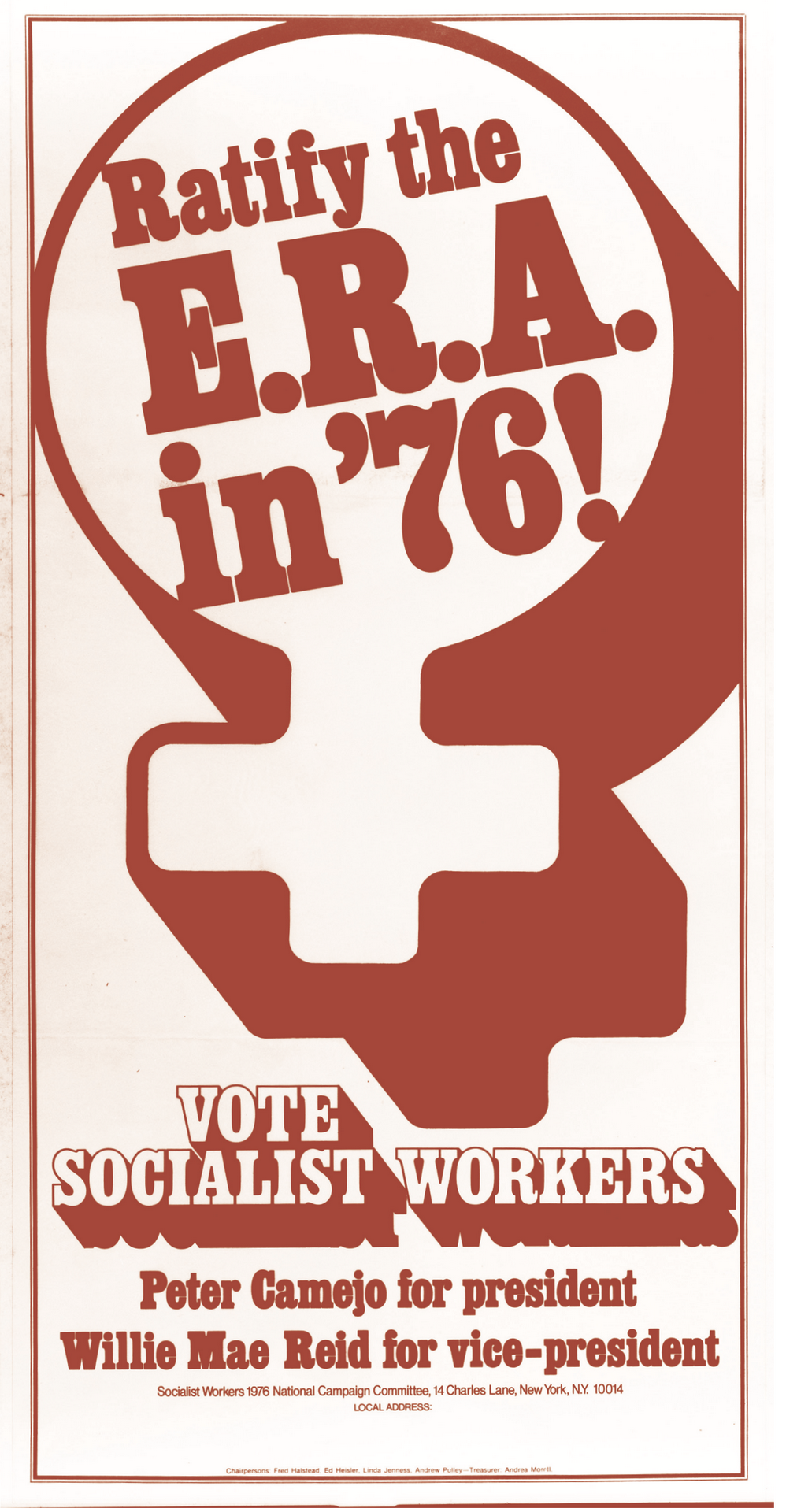

Socialist

Workers Party, National Campaign Committee

Ratify

the E.R.A. in '76. Vote Socialist Workers,

ca. 1976

Library

of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC

National

Organization for Women

National

ERA March sash, 1978

Fabric

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

ERA

March on Washington pin-back button,1978

Metal

Gift

of Beatrice J. Siegel, 2002.70.59

Ratify

the ERA pin-back button, 1977

Metal

Gift

of Betty Lerner. 2011.39.60

ERA

YES pin-back button, ca. 1970–75

Metal

Gift

of Norma P. Munn. 2002.68.18

National

Organization for Women, New York

We

Must Ratify by 6/30/82 pin-back button,1982

Metal

Gift

of Norma P. Munn, 2006.5.1

Stop-ERA Campaign

You Can’t Fool Mother Nature,

ca. 1974–77

Courtesy of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

Conservative women mobilized to defeat the Equal

Rights Amendment by arguing that legally mandated equality would force women to

abandon their traditional roles as wives and mothers. They warned that the ERA

would compel women to work outside the home to support their families and

subject them to the military draft.

Hat belonging to Bella Abzug, ca.

1970s

Straw

and pink tulle

Gift

of Judge Emily Jane Goodman, 2018.3

Activist and Congressional representative Bella Abzug

(1920-1998) began wearing instantly recognizable hats early in her career so

that men would take her seriously rather than mistaking her for a secretary.

“Who’s

afraid of equal rights?”

New York Times Magazine, April 11, 1976

New-York

Historical Society, Courtesy of Alice Kessler-Harris

Though it could easily be mistaken as a portrait of

conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, this New York Times Magazine cover depicts the stereotypical woman who

opposed the Equal Rights Amendment: a pearl-wearing, grocery-shopping,

middle-class housewife.

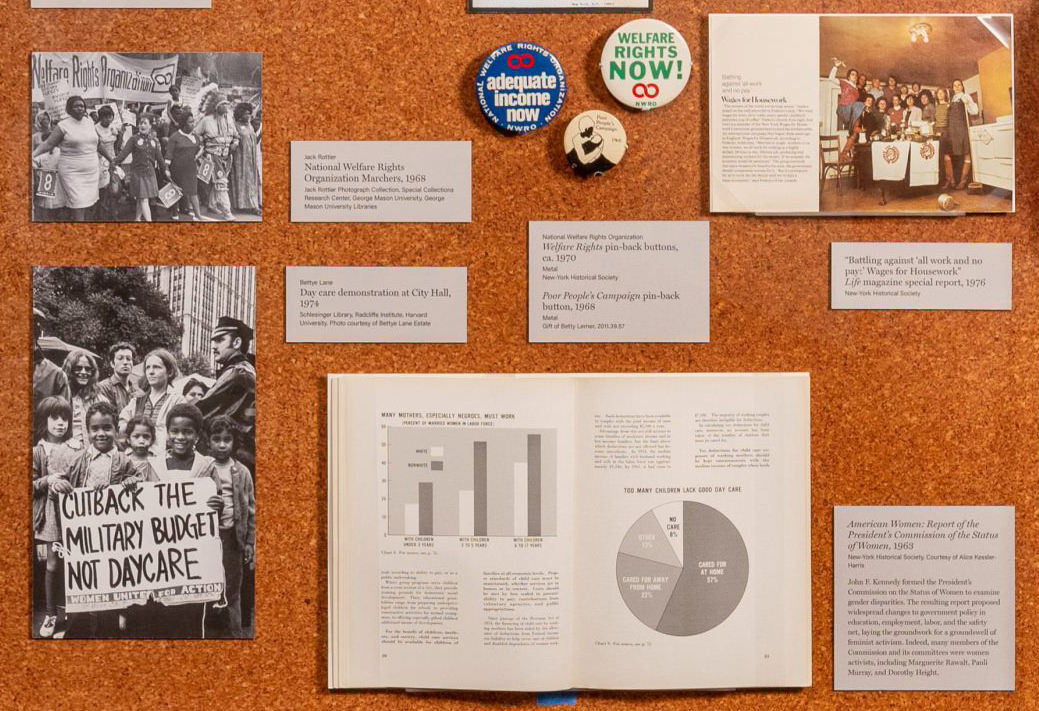

Defining Work

Work became a flashpoint for feminist activists in the 1970s. Recognizing economic freedom as integral to full citizenship, many sought to expand opportunities for women to work outside of the home. The 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited inequalities based on sex and race, while feminists used the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to successfully challenge barriers to women’s employment. Women also called for public daycare to make caregiving a societal responsibility. As their efforts opened doors and removed discriminatory barriers, the number of working women rose dramatically. Cautioning that a focus on legal equality might primarily benefit white, middle-class women, some sought to expand the very definition of work to include paid and unpaid caregiving and domestic labor. As a result, the welfare rights movement emerged at the intersection of the ongoing Black freedom movement, women’s liberation, and anti-poverty activism, and alongside related campaigns like Wages for Housework, the international grassroots collective. Many participants were single women of color, and they fought against punitive social policies that recognized paid labor over caregiving and tied benefits to increased surveillance. Women like Dorothy Bolden and Dolores Huerta also led movements to improve conditions in domestic and agricultural work.

Jack

Rottier

National Welfare Rights Organization

Marchers, 1968

Jack

Rottier Photograph Collection, Special Collections Research Center, George

Mason University,

George Mason University Libraries

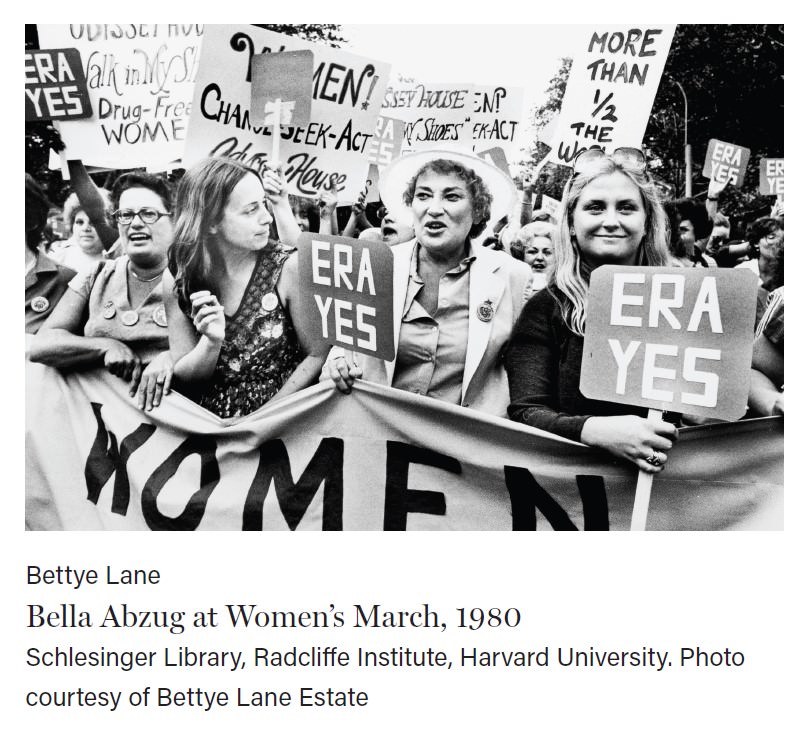

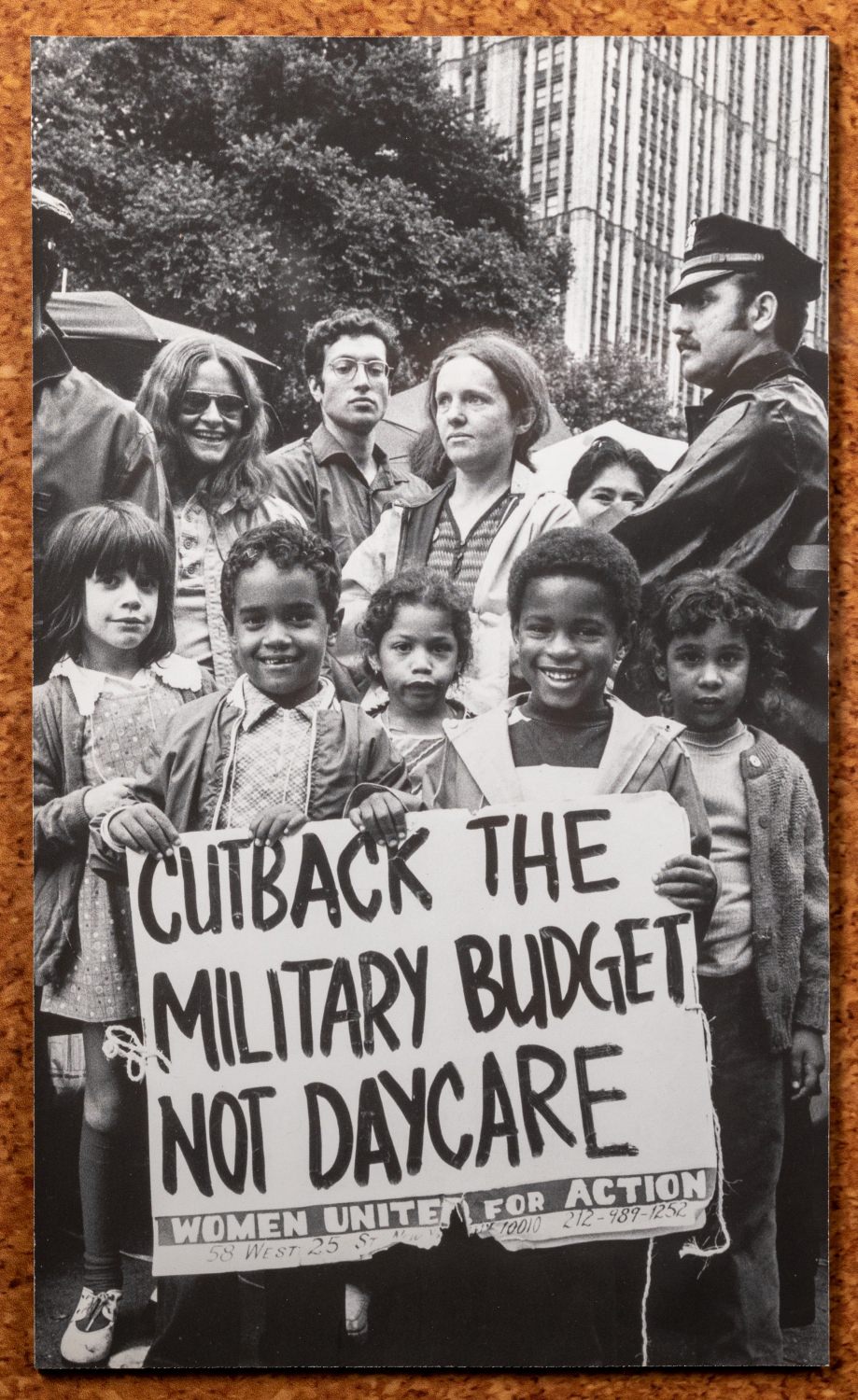

Bettye

Lane

Day care demonstration at City Hall, 1974

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. Photo courtesy of Bettye Lane

Estate

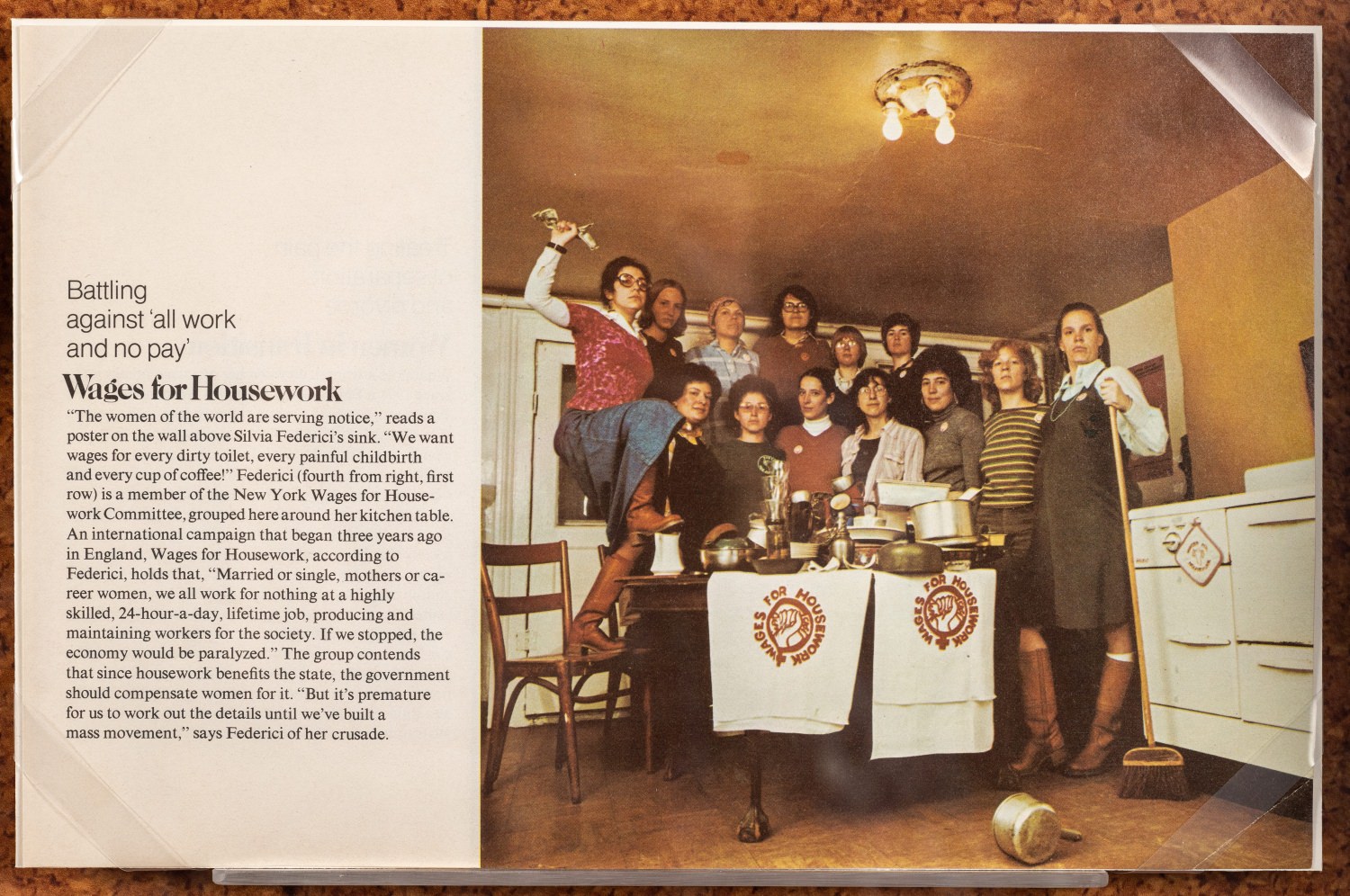

“Battling

against ‘all work and no pay’: Wages for Housework” Life magazine special report, 1976

New-York

Historical Society

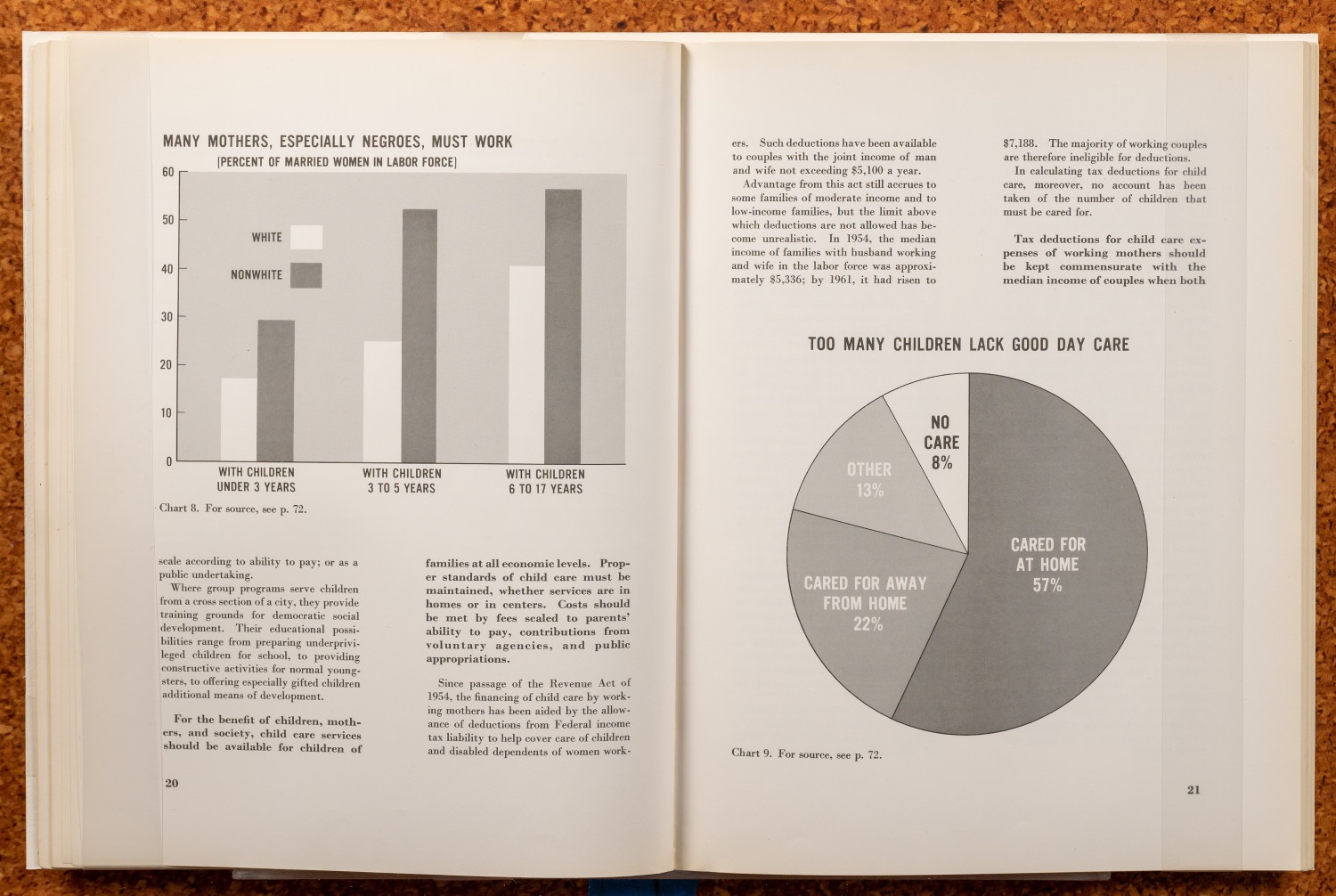

American

Women: Report of the President’s Commission of the Status of Women, 1963

New-York

Historical Society, Courtesy of Alice Kessler-Harris

John F. Kennedy

formed the President’s Commission on the Status of Women to examine gender

disparities. The resulting report proposed widespread changes to government

policy in education, employment, labor, and the safety net, laying the

groundwork for a groundswell of feminist activism. Indeed, many members of the

Commission and its committees were women activists, including Marguerite

Rawalt, Pauli Murray, and Dorothy Height.

National

Welfare Rights Organization

Welfare

Rights pin-back buttons, ca.

1970-75

Metal

New-York

Historical Society

Poor

People’s Campaign pin-back button, 1968

Metal

Gift

of Betty Lerner, 2011.39.57

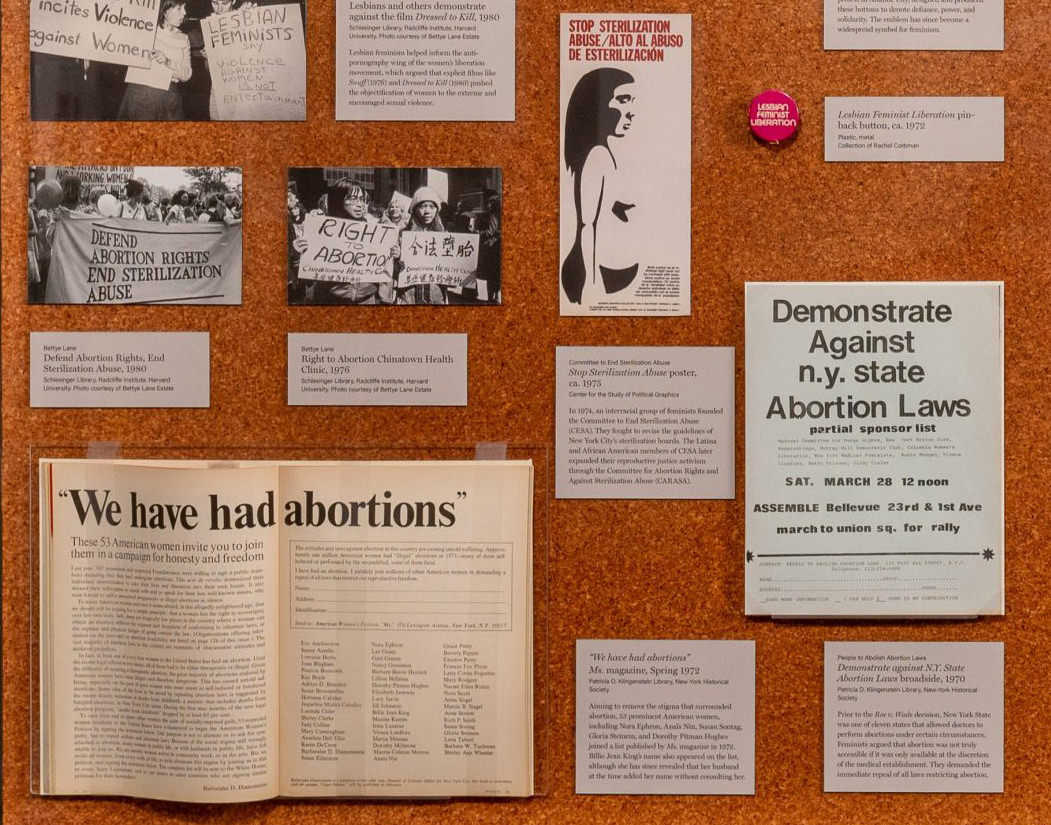

Reproductive Rights

With FDA approval of the first oral contraceptive in 1960, questions of control over women’s bodies took on new dimensions. The Pill helped disconnect sexual activity from childbirth and aided the women’s liberation movement’s fight for sexual and reproductive self-determination. Conservative women simultaneously mobilized against feminist gains. Women also demanded their voices be heard in the courtroom. Inspired by a 1969 Redstockings “speak-out,” attorney Florynce Kennedy called dozens of women who had been injured by illegal abortions to testify in a New York State case. This pioneering legal strategy, alongside public protests, drew attention to how restrictive abortion laws oppressed women. In 1973, Kennedy’s techniques were adopted for the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade, which led to the nationwide legalization of abortion. Black feminists like Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm expanded the discussion to include access to contraceptives and affordable child care, anti-poverty measures, and an end to sterilization abuse, which fell disproportionately on Black, Native American, and Latina women. Until 1977, poverty, single motherhood, incarceration, and the receipt of welfare or Medicaid benefits would remain legal grounds for sterilization.

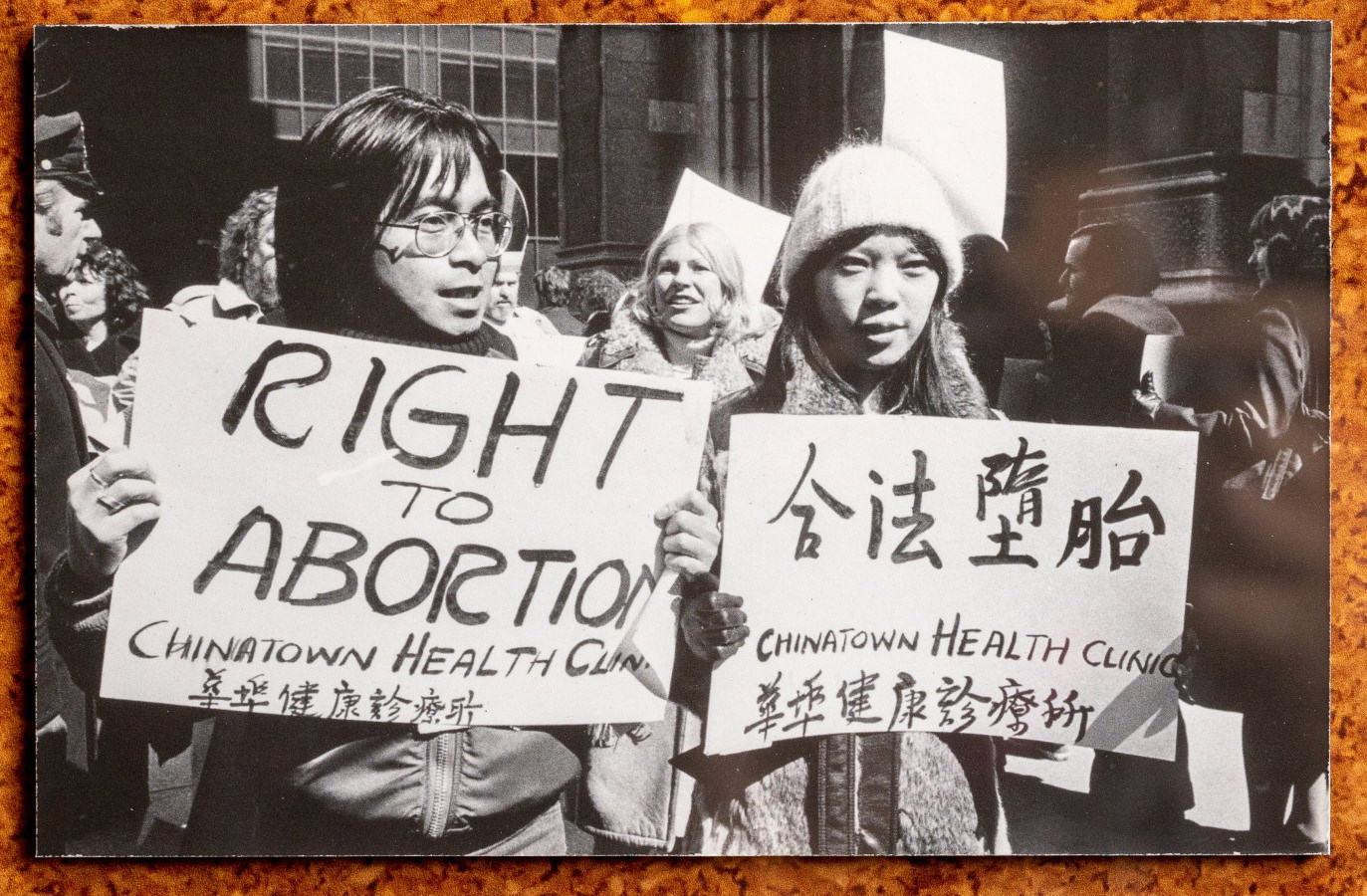

Bettye

Lane

Right to Abortion Chinatown Health

Clinic, 1976

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Photo courtesy of Bettye Lane

Estate

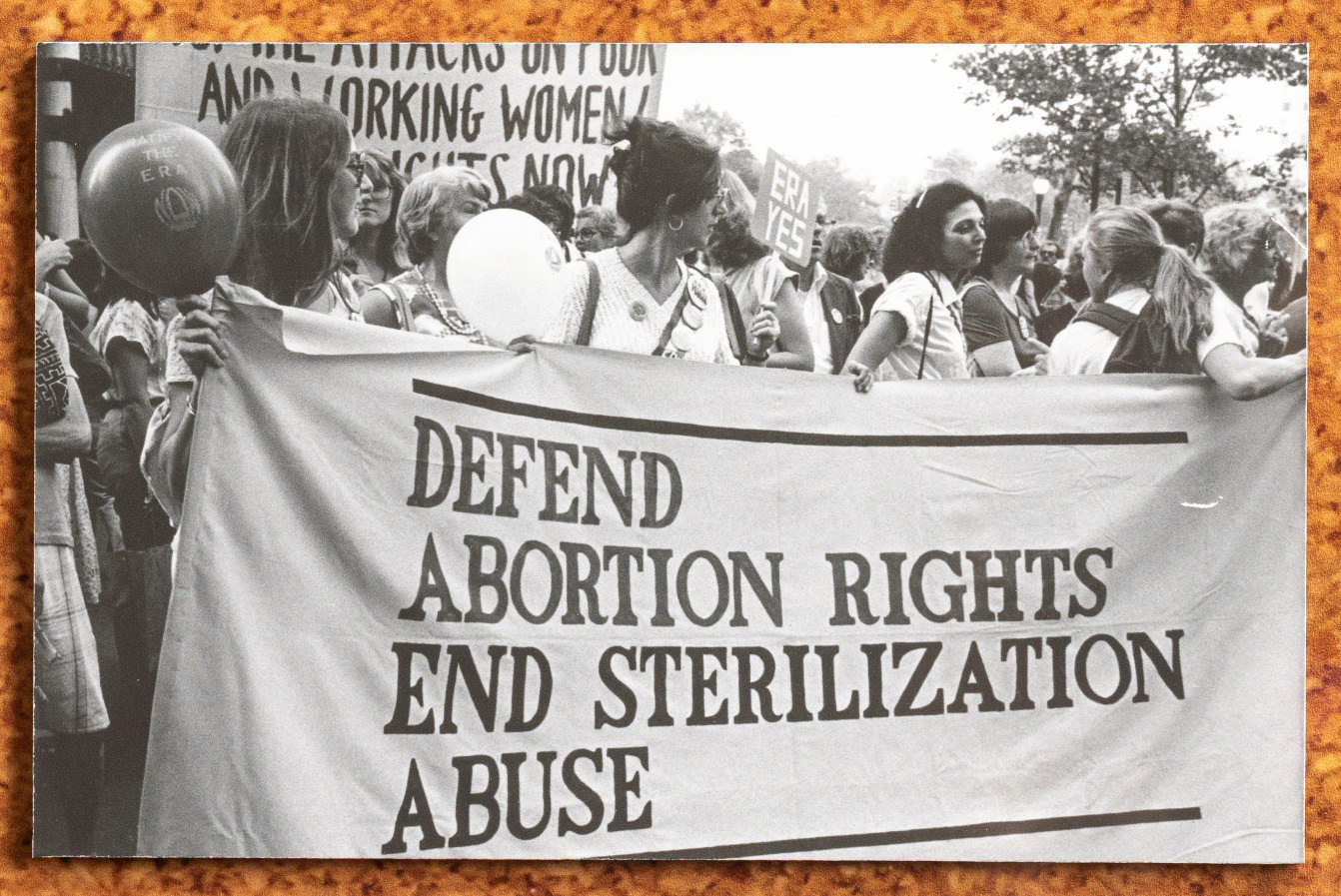

Bettye

Lane

Defend Abortion Rights, End

Sterilization Abuse, 1980

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Photo courtesy of Bettye Lane

Estate

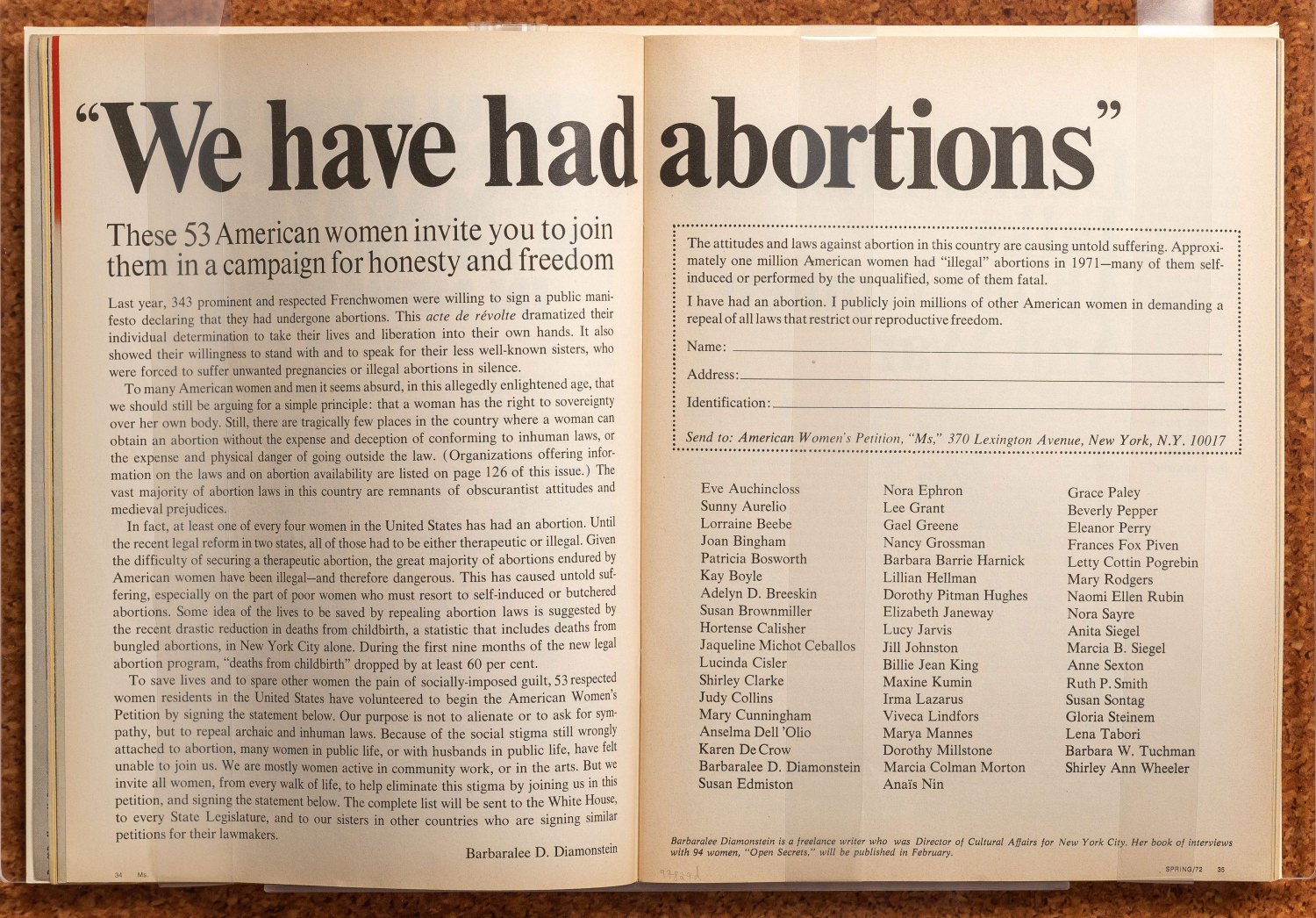

“We

have had abortions”

Ms. magazine, Spring 1972

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Aiming to remove the stigma that surrounded abortion,

53 prominent American women, including Nora Ephron, Anaïs Nin, Susan Sontag,

Gloria Steinem, and Dorothy Pitman Hughes joined a list published by Ms. magazine in 1972. Billie Jean King’s

name also appeared on the list, although she has since revealed that her

husband at the time added her name without consulting her.

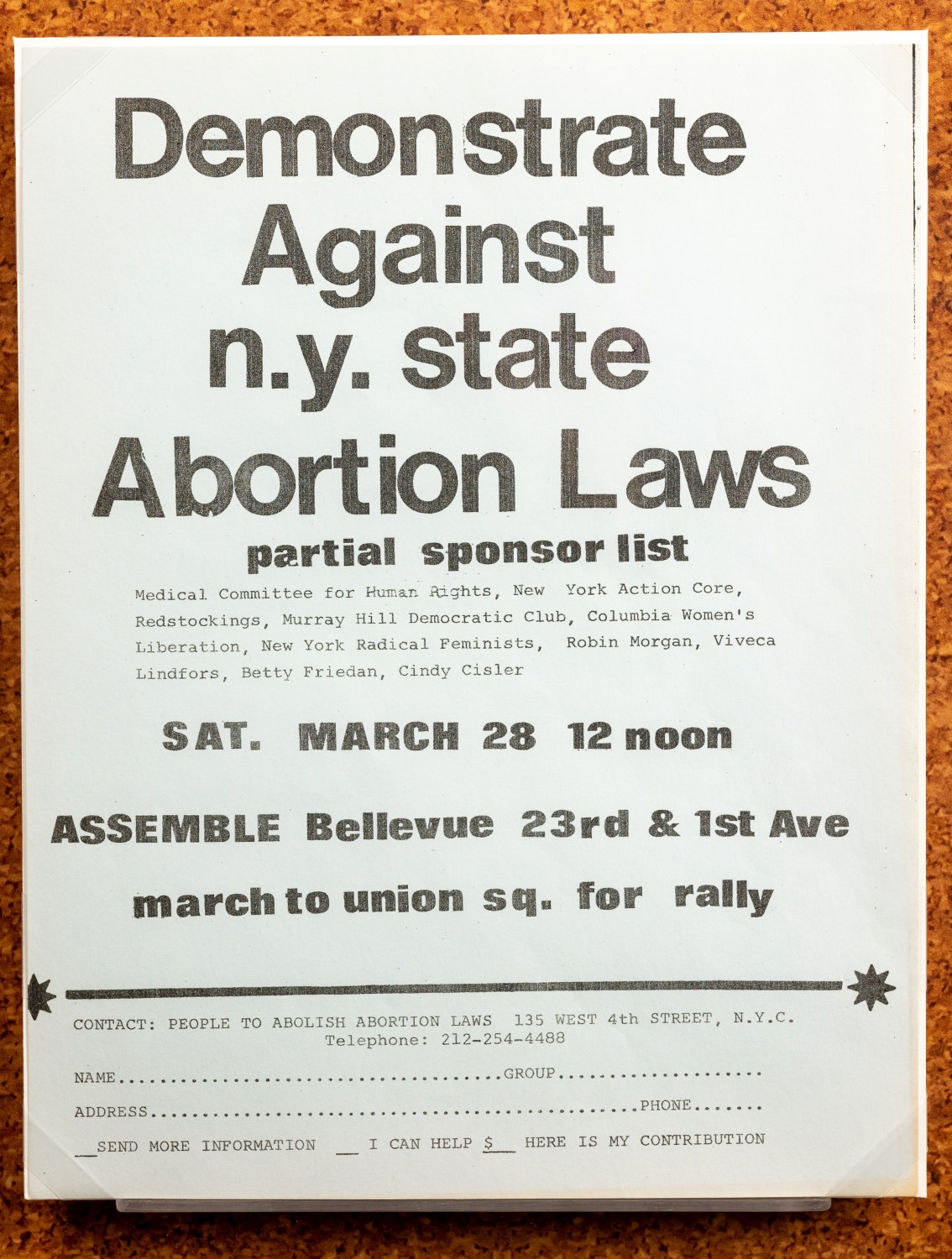

People

to Abolish Abortion Laws

Demonstrate

against N.Y. State Abortion Laws broadside, 1970

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Prior to the Roe

v. Wade decision, New York State was one of eleven states that allowed

doctors to perform abortions under certain circumstances. Feminists argued that

abortion was not truly accessible if it was only available at the discretion of

the medical establishment. They demanded the immediate repeal of all laws

restricting abortion.

Breaking the Silence About

Male Violence

For many women, “the personal is political” slogan applied to domestic abuse. In January 1971, thirty New York women publicly testified about the wide array of bodily violations they had experienced, from street harassment to rape. They rejected the notion that violence was a normal part of sex, and redefined rape as an act of control deployed by men to intimidate women. In 1972, feminists in Washington, DC, and Berkeley, California organized the first rape crisis centers. By 1980, 500 centers existed nationwide. Battered women’s shelters opened to provide refuge to those who escaped abusive partners, and pressured law enforcement to take women’s accusations seriously. Staff counseled rape survivors and encouraged women to overcome passivity and physically resist attackers. Feminists embraced the self-defense of women of color, who were statistically most likely to be victimized by rape and abuse. Between 1974 and 1979, they rallied in support of Inez García, Joan Little, and Yvonne Wanrow, all women of color who had been arrested and incarcerated for killing rapists.

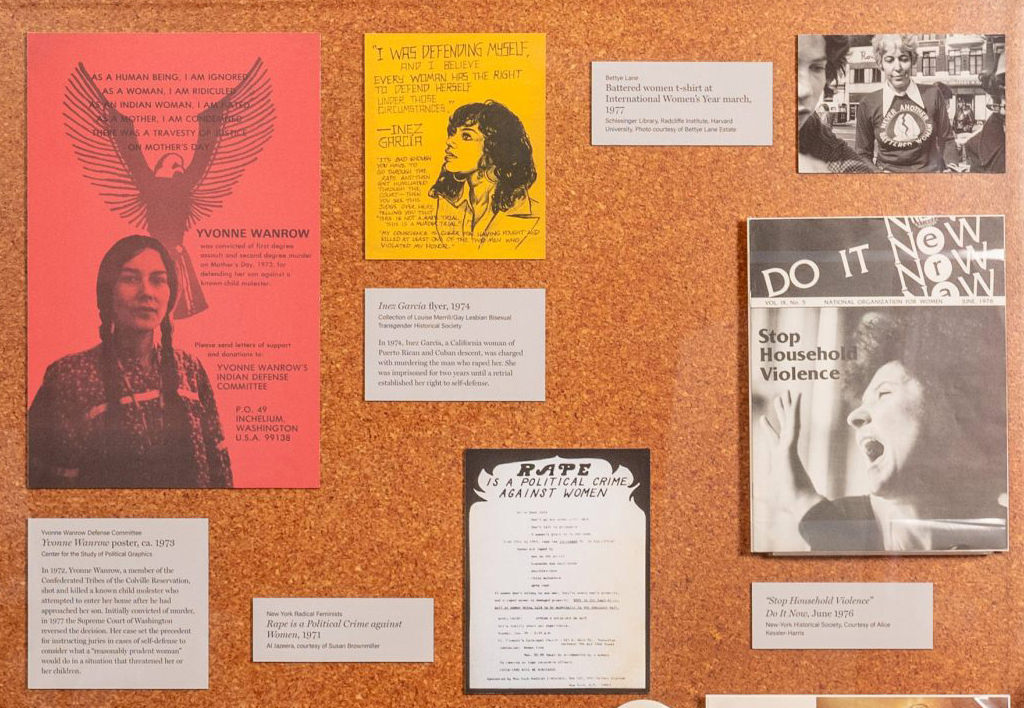

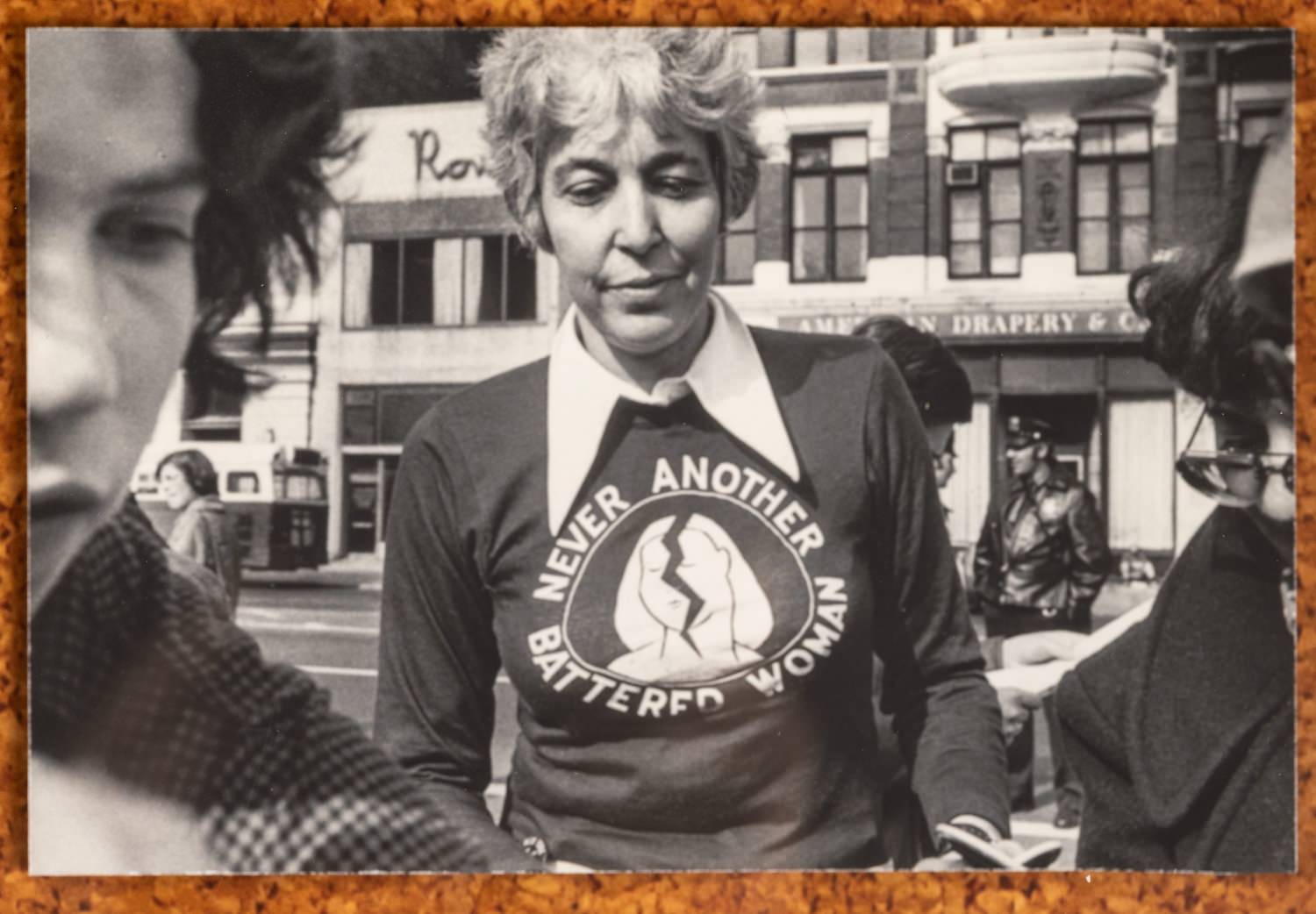

Bettye

Lane

Battered women t-shirt at International

Women's Year march,1977

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Photo courtesy of Bettye Lane

Estate

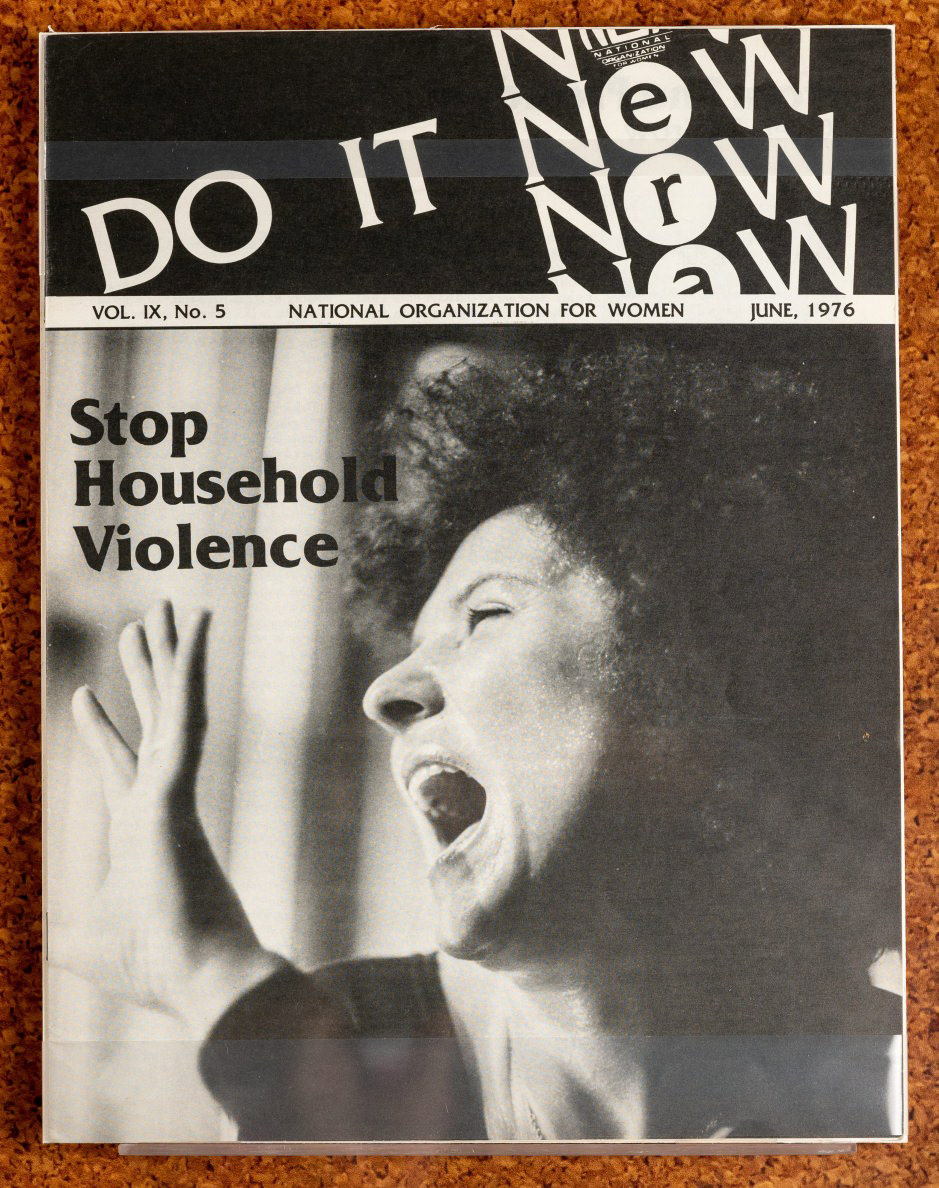

“Stop

Household Violence”

Do It Now, June 1976

New-York

Historical Society, Courtesy of Alice Kessler-Harris

Yvonne

Wanrow Defense Committee

Yvonne

Wanrow poster, ca. 1973

Collection

of Center for the Study of Political Graphics

In 1972, Yvonne Wanrow, a member of the Confederated

Tribes of the Colville Reservation, shot and killed a known child molester who

attempted to enter her home after he had approached her son. Initially

convicted of murder, in 1977 the Supreme Court of Washington reversed the

decision. Her case set the precedent for instructing juries in cases of

self-defense to consider what a “reasonably prudent woman” would do in a situation

that threatened her or her children.

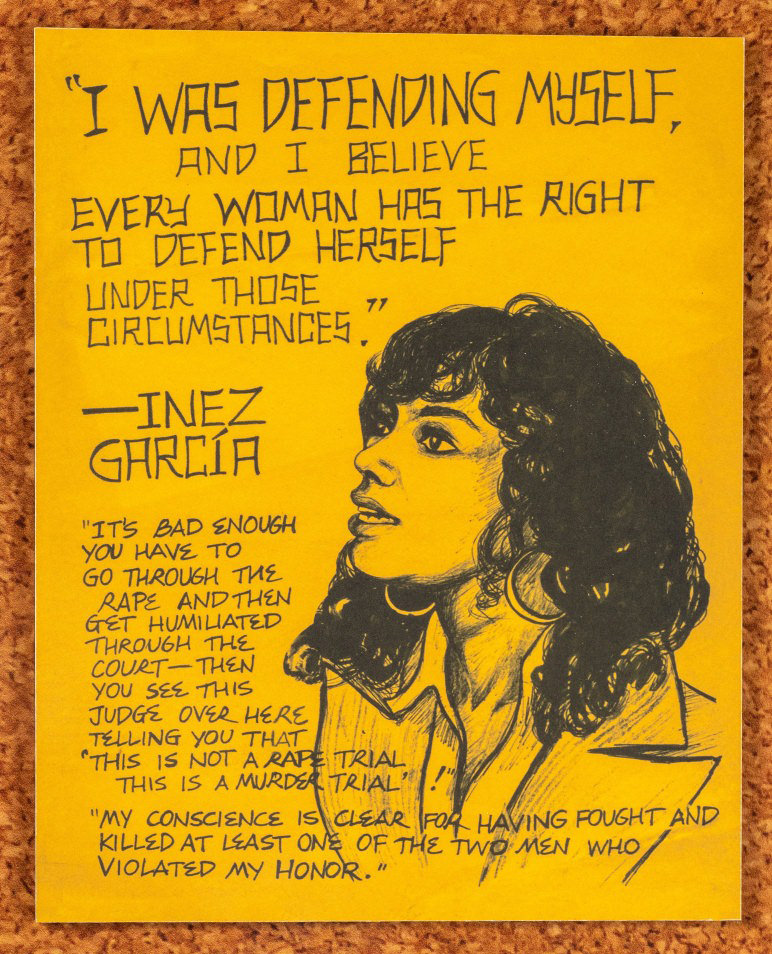

Inez

García

flyer,1974

Collection

of Louise Merrill/Gay Lesbian Bisexual Transgender Historical Society

In 1974, Inez García,

a California woman of Puerto Rican and Cuban descent, was charged with

murdering the man who raped her. She was imprisoned for two years until a

retrial established her right to self-defense.

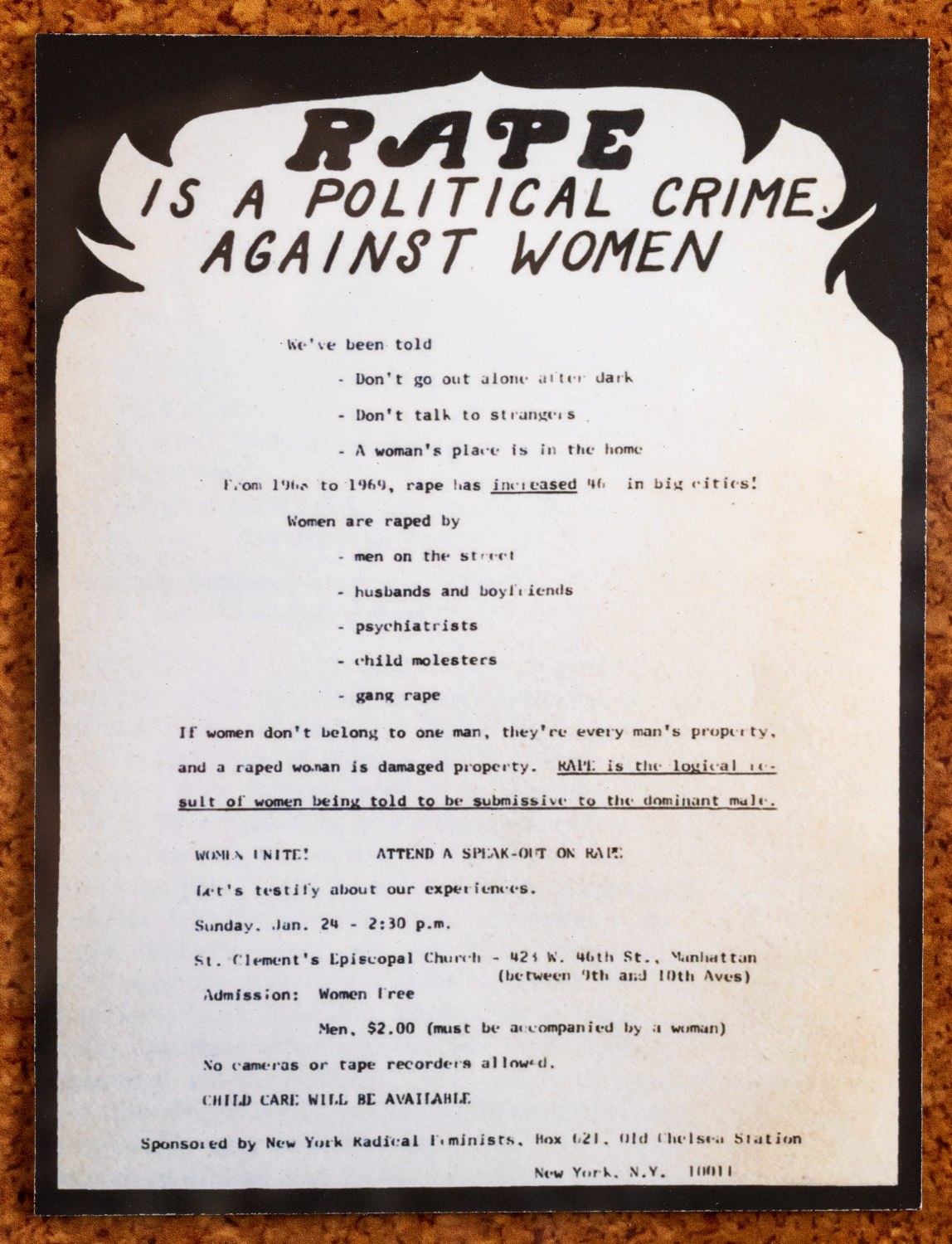

New York Radical Feminists

Rape is a Political Crime against

Women, 1971

Al Jazeera, courtesy of Susan

Brownmiller

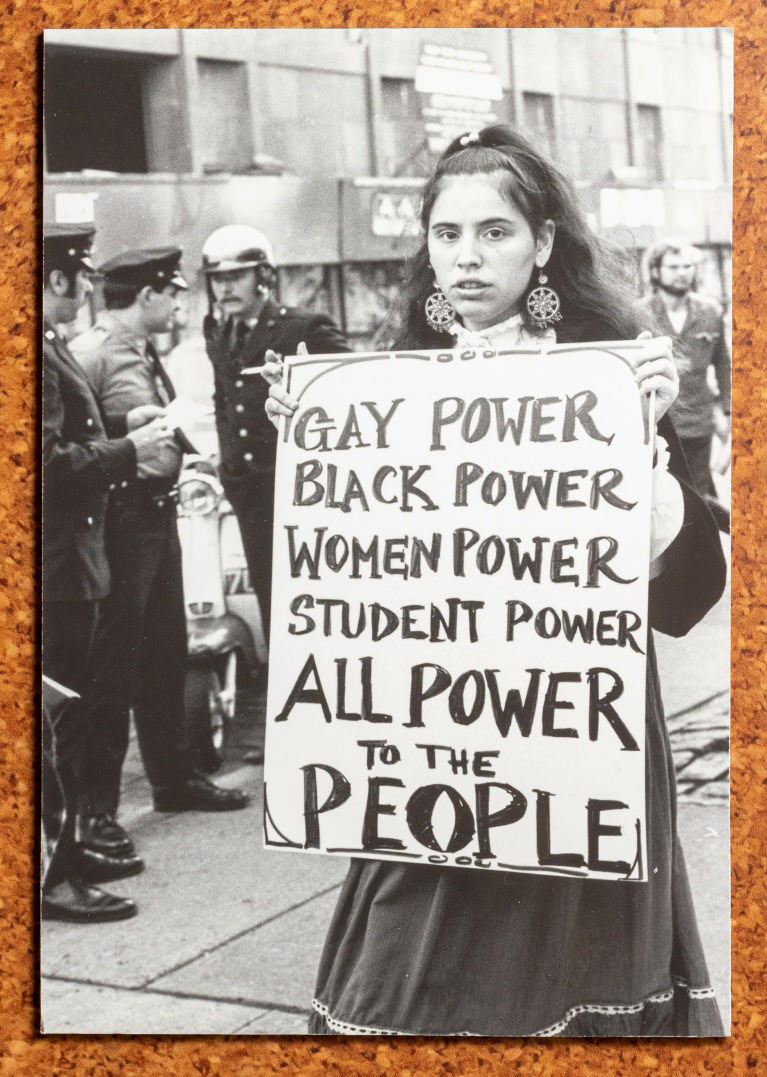

Sexual Politics

Women’s liberationists illuminated how the seemingly private world of sexual relations was riddled with power struggles. At the 1968 Miss America pageant, feminists protested the sexual objectification of women with placards featuring advertisements that compared women to prime cuts of meat. Some lesbians in the movement further argued that heterosexuality itself promoted sexism in American culture. The 1969 Stonewall uprising compounded these debates, catalyzing the movement for gay liberation that was rallied in part by transgender women like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, the founders of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). In 1970, a group of radical lesbian feminists interrupted the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City. Their “Lavender Menace” t-shirts challenged Betty Friedan’s remark that lesbians in feminist organizations threatened to discredit the entire movement. They countered that lesbians were actually in the vanguard of the struggle for women’s liberation for not participating in heterosexual culture. Such challenges profoundly shaped the feminist organizations of women of color, such as Boston’s Combahee River Collective and New York City’s Salsa Soul Sisters.

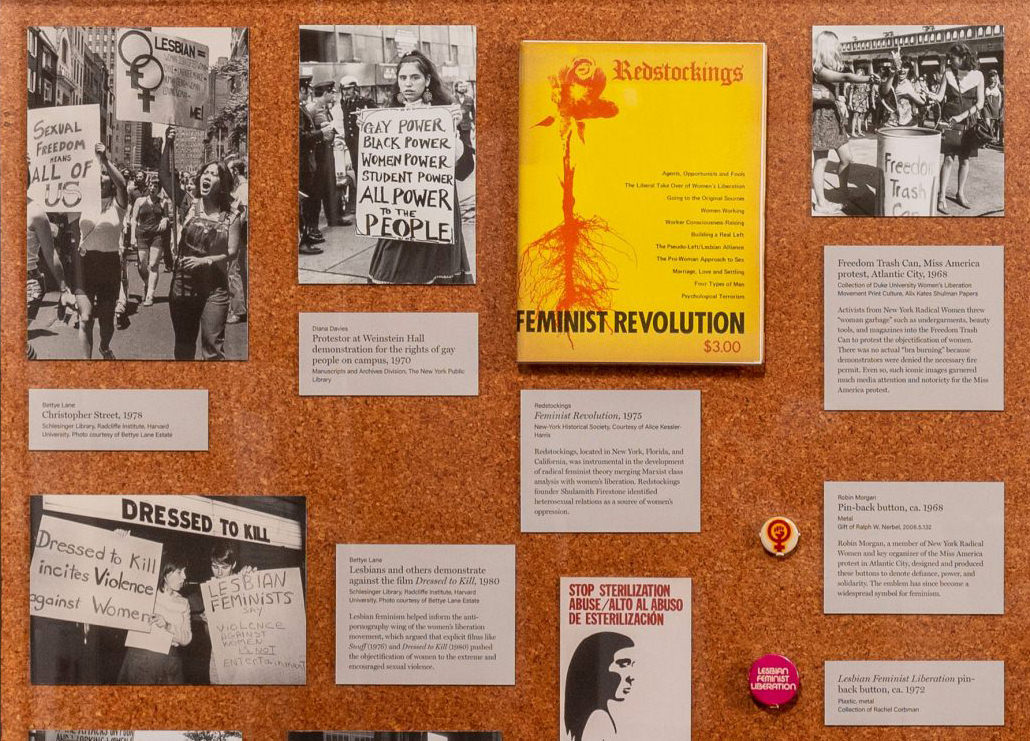

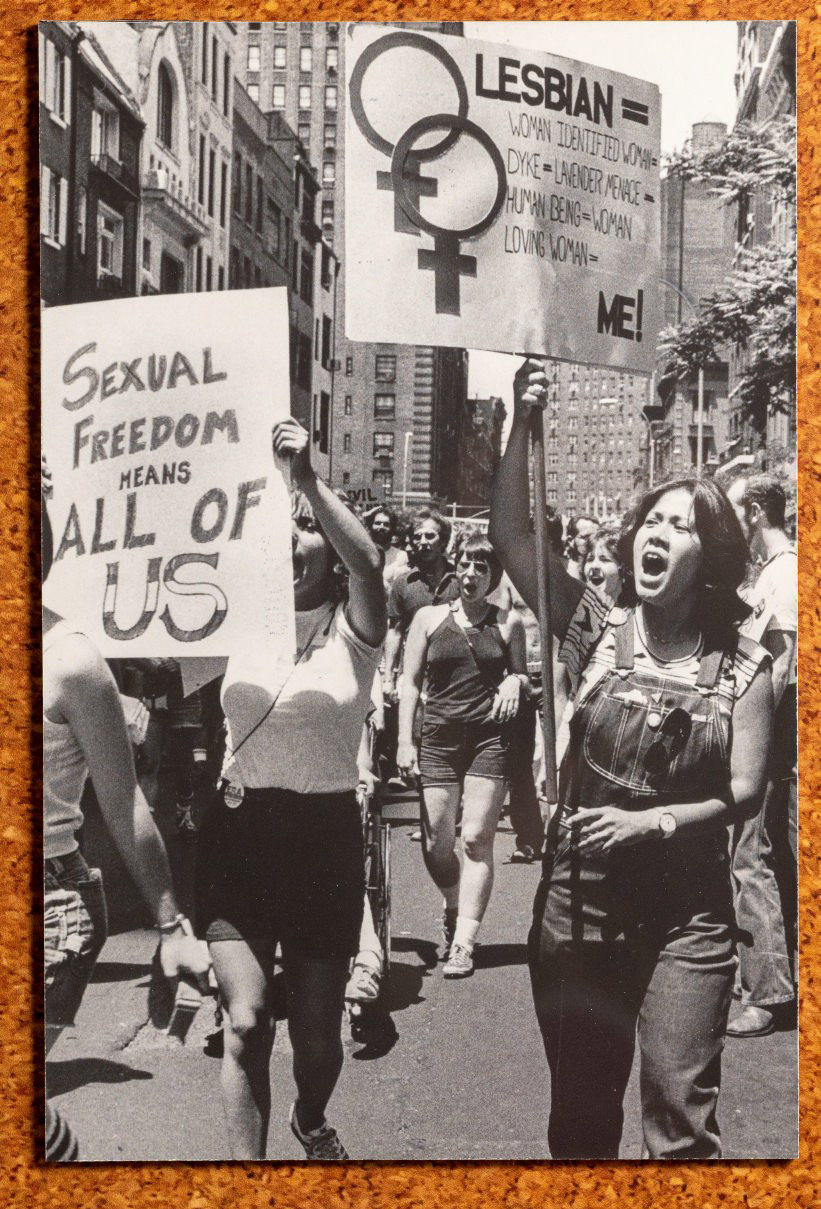

Bettye

Lane

Christopher Street, 1978

Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. Photo courtesy of Bettye Lane

Estate

Diana

Davies

Protestor at Weinstein Hall

demonstration for the

rights of gay people on campus, 1970

Manuscripts

and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

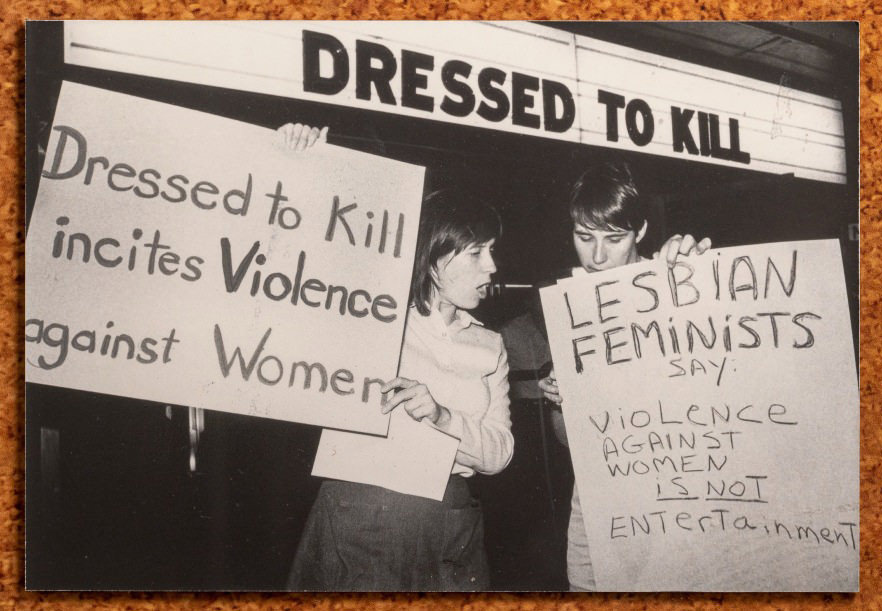

Bettye

Lane

Lesbians and others demonstrate against the film

Dressed to Kill, 1980

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Photo courtesy of Bettye Lane Estate

Lesbian feminism helped inform the anti-pornography wing of the women’s liberation movement,

which argued that explicit films like Snuff (1976) and Dressed to Kill (1980) pushed the objectification

of women to the extreme and encouraged sexual violence.

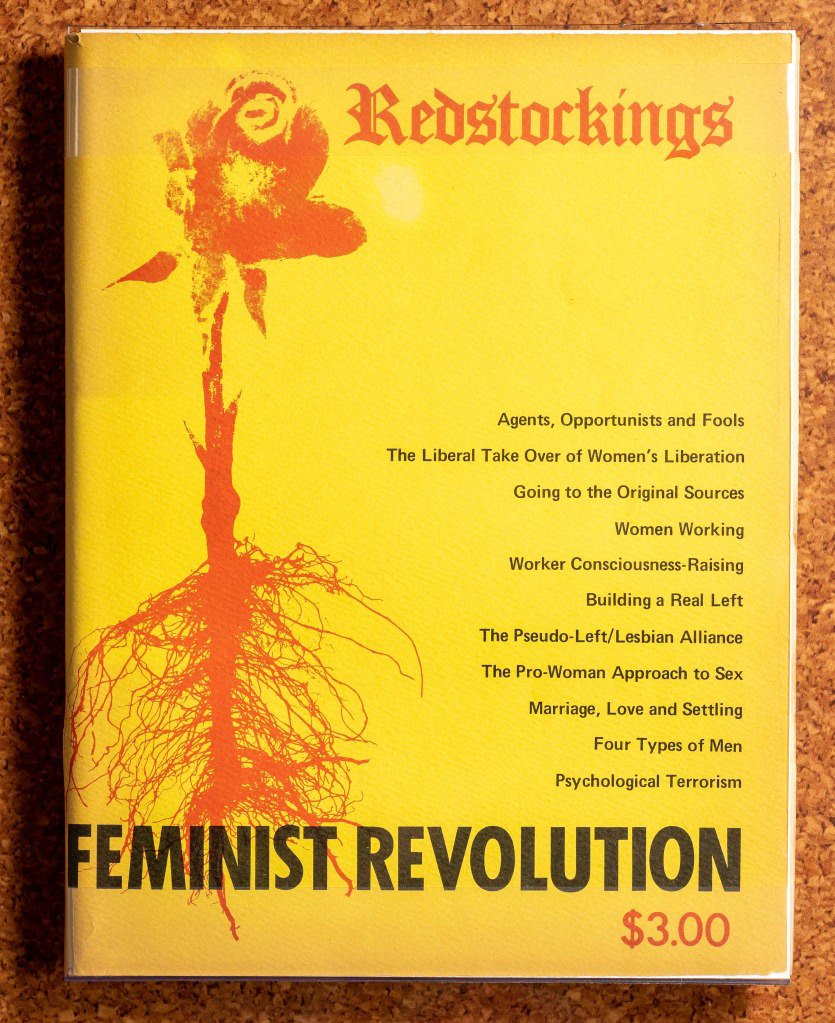

Redstockings

Feminist

Revolution,1975

New-York

Historical Society, Courtesy of Alice Kessler-Harris

Redstockings,

located in New York, Florida, and California, was instrumental in the development

of radical feminist theory merging Marxist class analysis with women’s

liberation. Redstockings founder Shulamith Firestone identified heterosexual

relations as a source of women’s oppression.

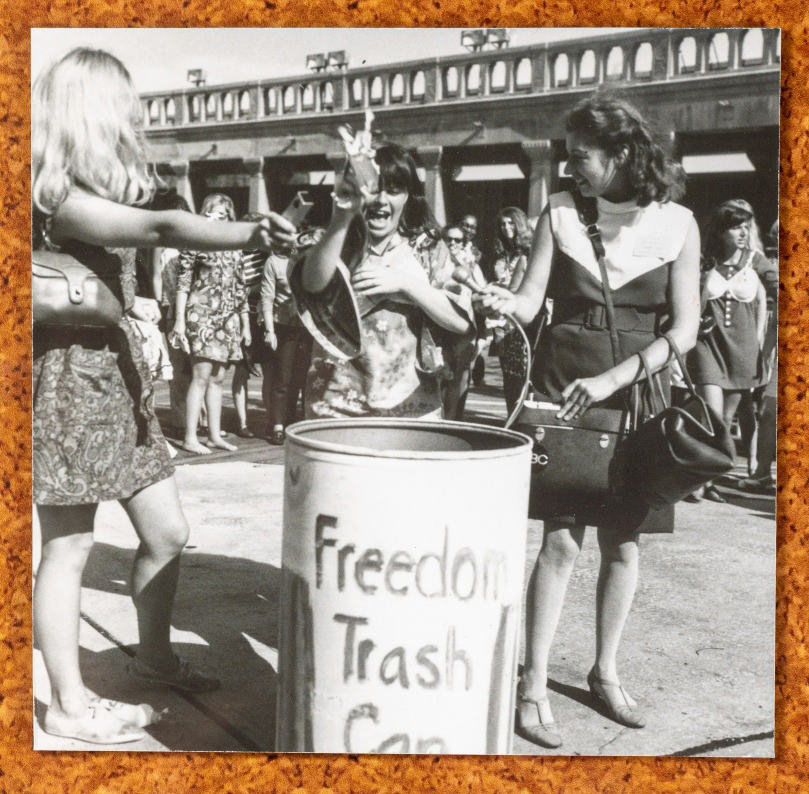

Freedom Trash Can, Miss America protest,

Atlantic City, 1968

Collection

of Duke University Women’s Liberation Movement Print Culture, Alix Kates

Shulman Papers

Activists

from New York Radical Women threw “woman garbage” such as undergarments, beauty

tools, and magazines into the Freedom Trash Can to protest the objectification

of women. There was no actual “bra burning” because demonstrators were denied

the necessary fire permit. Even so, such iconic images garnered much media

attention and notoriety for the Miss America protest.

Pin-back button, ca. 1968

Metal

Gift of Ralph W. Nerbel, 2006.5.132

Robin Morgan, a member of New York

Radical Women and key organizer of the Miss America protest in Atlantic City,

designed and produced these buttons to denote defiance, power, and solidarity.

The emblem has since become a widespread symbol for feminism.

Lesbian

Feminist Liberation

pin-back button,ca. 1972

Plastic, metal

Collection

of Rachel Corbman