click for 360 tour

Filmed reenactment of Frances Harper’s 1866 speech at the 11th National Woman’s Rights Convention

Ariana DeBose as Frances Harper, 2019

Special thanks to the CUNY School of Professional Studies

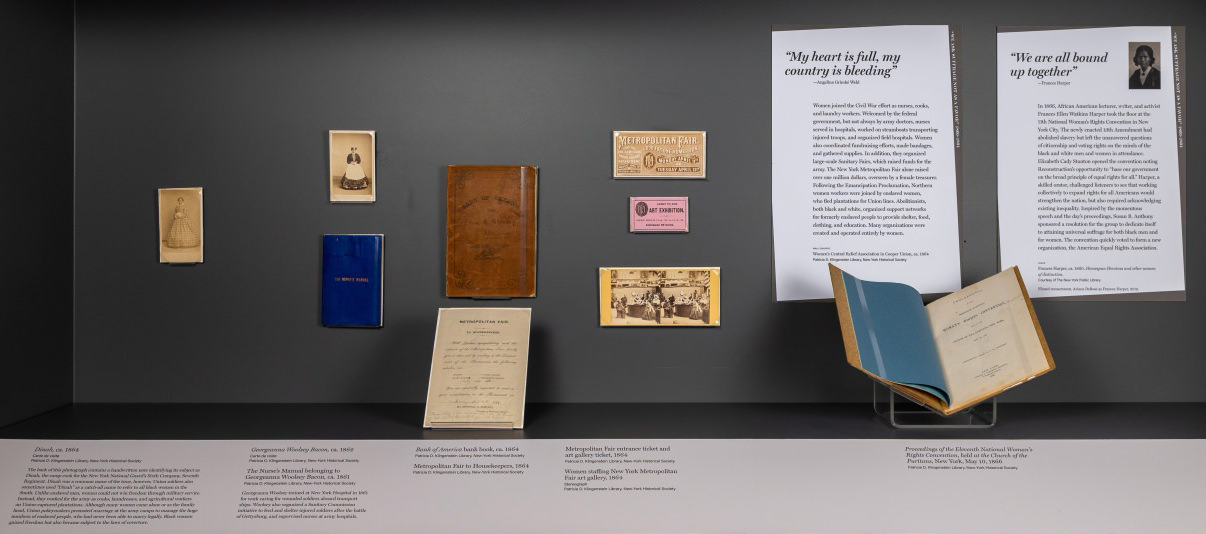

The Nurse’s Manual belonging to

Georgeanna Woolsey Bacon, ca. 1861

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Georgeanna

Woolsey trained at New York Hospital in 1861 for work caring for wounded

soldiers aboard transport ships. Woolsey also organized a Sanitary Commission

initiative to feed and shelter injured soldiers after the battle of Gettysburg,

and supervised nurses at army hospitals.

“My heart is full, my country

is bleeding”

- Angelina Grimké Weld

Women joined the Civil War effort as nurses, cooks, and laundry workers. Welcomed by the federal government, but not always by army doctors, nurses served in hospitals, worked on steamboats transporting injured troops, and organized field hospitals. Women also coordinated fundraising efforts, made bandages, and gathered supplies. In addition, they organized large-scale Sanitary Fairs, which raised funds for the army. The New York Metropolitan Fair alone raised over one million dollars, overseen by a female treasurer. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, Northern women workers were joined by enslaved women, who fled plantations for Union lines. Abolitionists, both Black and white, organized support networks for formerly enslaved people to provide shelter, food, clothing, and education. Many organizations were created and operated entirely by women.

Women staffing New York Metropolitan

Fair art gallery, 1864

Stereograph

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

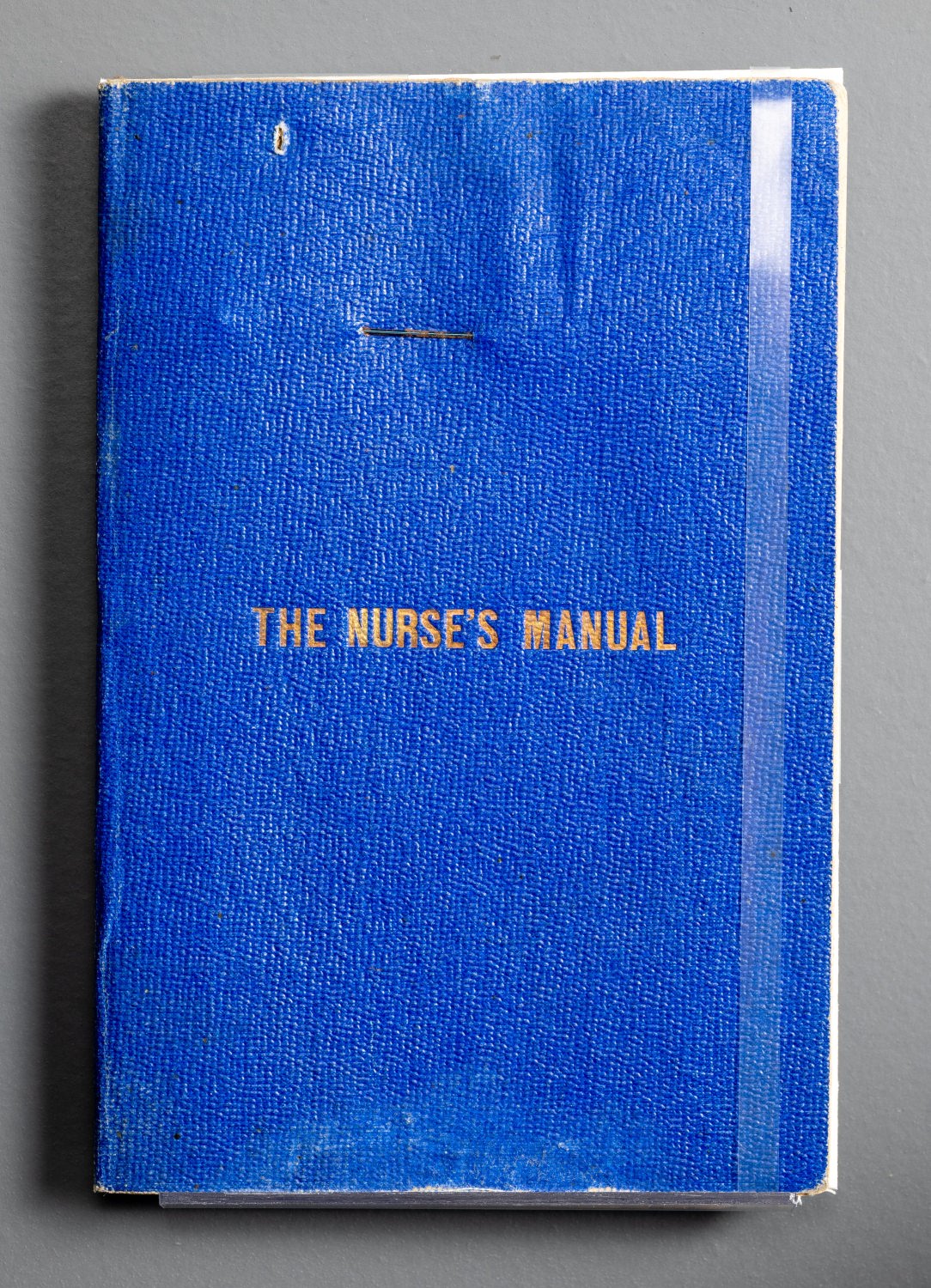

The

Facts in the Case, ca. 1888

Chicago:

Woman's Temperance Publication Association

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

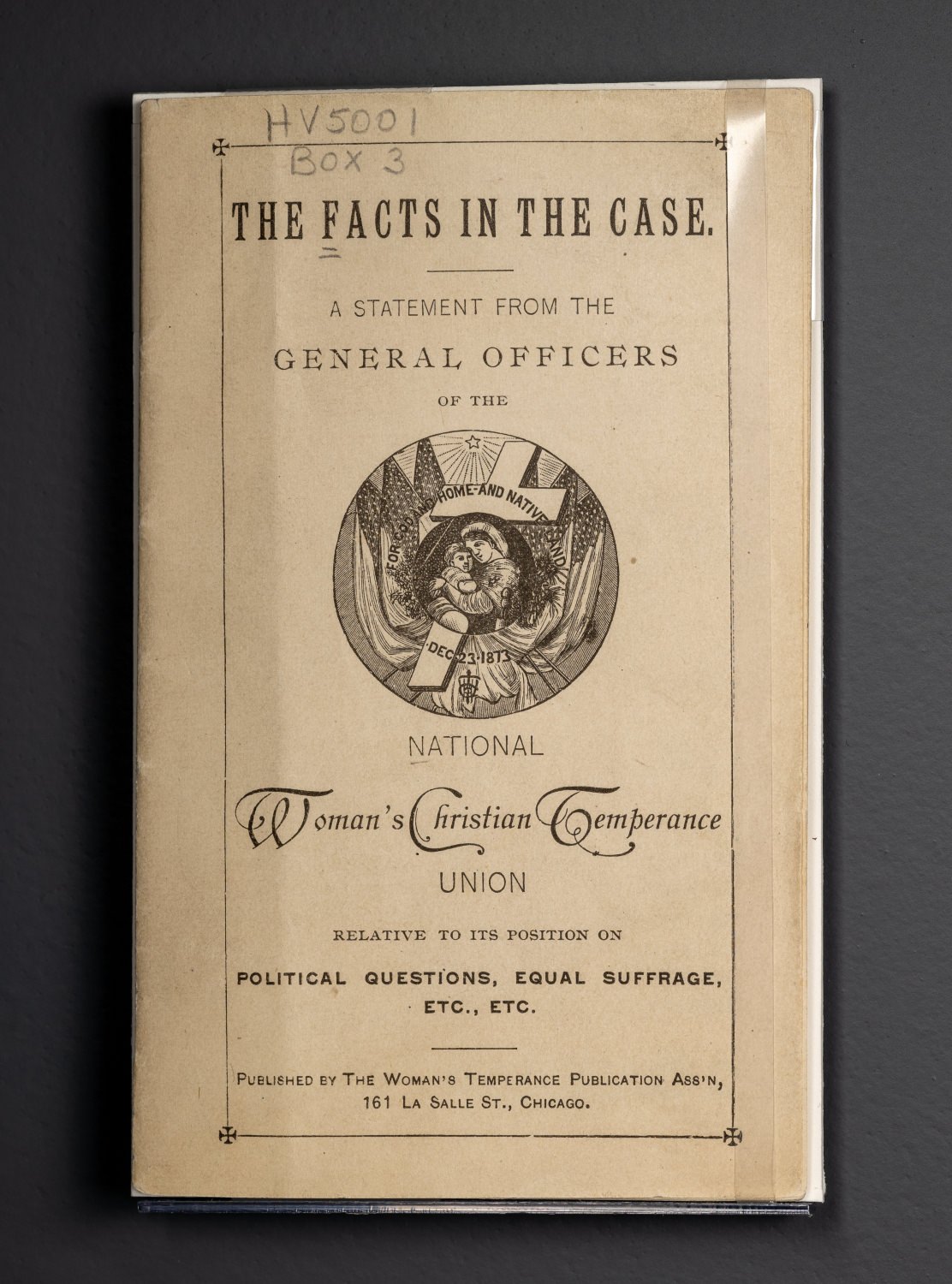

Temperance crusaders in front of grocery, 1873

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection (SC

1887)

Frances

Harper WCTU branch, Seattle, ca. 1895

Twice

Sold, Twice Ransomed by Mr. and Mrs. L.P. Ray

The Burke Library at Union Theological

Seminary,

Columbia University in the City of New York