click for 360 tour

“Our Souls

Have Caught the Flame”

- Maria W. Stewart

One hundred years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, American women mobilized to champion social reform through long-standing traditions of mutual aid, benevolence, and charity. At a time of profound political, social, and economic change, women—without benefit of the vote—claimed a role in the success, stability, and survival of the nation. Fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, Black and white women founded hundreds of voluntary organizations, ranging in focus from local antipoverty programs to labor reform to a nationwide campaign against slavery. Yet lack of political power constrained women’s ability to affect change. By 1848, attendees at a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY declared their intention to seek equality and full citizenship in every aspect of their lives—including the vote.

“Shake the tree of liberty”

-Sarah Forten

Free Black women were crucial to the anti-slavery movement. Close-knit networks of church, kin, and friends helped them circulate abolitionist ideas throughout the US. In large cities and small towns, they raised money, formed literary societies, published in journals, established mutual aid associations, supported the national Colored Convention movement, and took active roles in anti-slavery organizations. Many of Philadelphia’s prominent free Black women were members of both the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, notable for electing Black and white officers. In 1832, Maria W. Stewart became the first American-born woman to lecture publicly to mixed audiences on political themes of emancipation, racial prejudice, and women’s rights. Later, other African American women, including Sarah Mapps Douglass, Sarah Parker Remond, Sojourner Truth, and Frances Watkins Harper, also became sought-after orators, calling for women’s empowerment and an end to slavery.

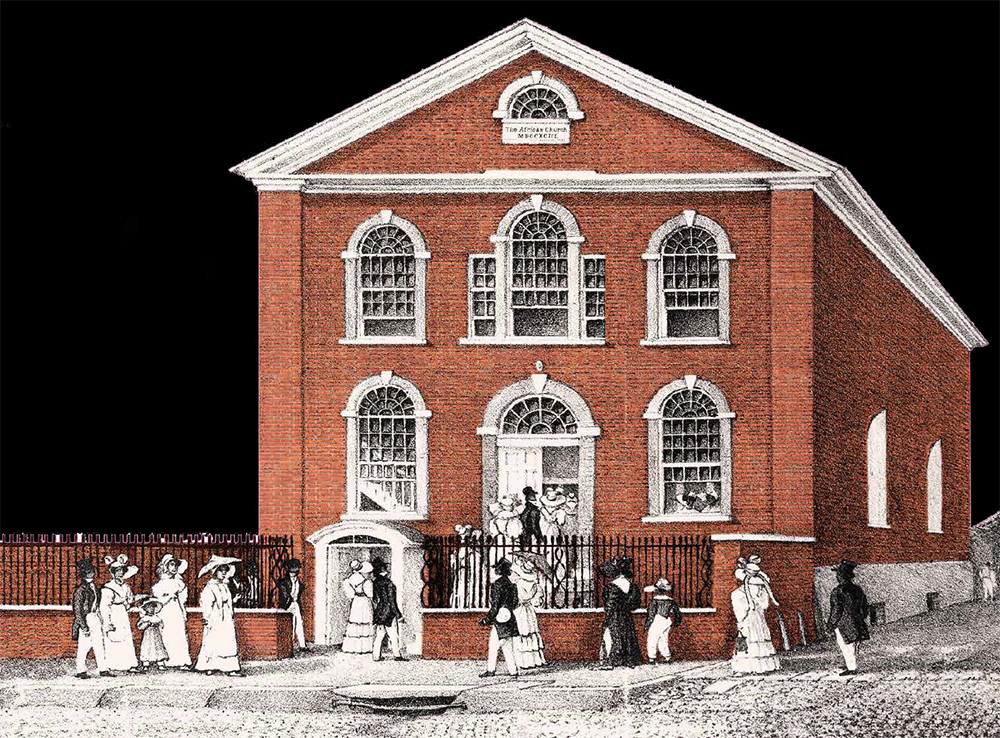

William L. Breton

A

Sunday morning view of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, 1829

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

“In the habit of slavery are concentrated the strongest evils of human nature”

-Lydia Maria Child

Abolitionist publications, including Frederick Douglass’s North Star, William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, Maria Weston Chapman’s Liberty Bell, and even a children’s alphabet described the sexual assault of enslaved women and the forced separation of their families to enlist readers’ moral opposition to slavery. Anti-slavery poems, essays, lectures, and novels by Black and white authors sought to awaken empathy towards enslaved mothers and children who were separated and sold. Many such publications were available at anti-slavery bazaars, first organized in 1834 by a group of Boston women. By the late 1850s, Black and white women in dozens of cities and towns had formed abolitionist sewing circles, solicited donations, and organized anti-slavery fairs. The funds supported publications and traveling lecturers, assisted fugitive slaves, and endowed schools for African American children. Such volunteer work advanced women’s skills in leadership, organizing, lobbying, and fundraising that they soon would translate into the political arena.

Animated

graphic treatment of Declaration of

Sentiments

(selected text)

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among

the Lowly

Boston: John P. Jewett & Co.,

1853

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library,

New-York Historical Society

Between 1820 and 1860, the US experienced a great

surge in literacy. Among an expanding market for magazines, tracts, newspapers,

and books, Uncle Tom’s Cabin stands

out for its unprecedented success. First published in 1852, it sold 300,000

copies within a year (and has never gone out of print). Like many antislavery

authors, Harriet Beecher Stowe used religious appeals and sentimental language

to evoke sympathy for the enslaved characters and persuade readers to join the

abolitionist cause.

Julia Griffiths, editor

Autographs for Freedom, second series

Rochester, NY: Rochester Ladies’

Anti-Slavery Society, 1854

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library,

New-York Historical Society

After escaping from slavery in 1838, Frederick

Douglass became one of the most prominent speakers in the abolitionist

movement. He also championed women’s political rights, attending the 1848

Convention at Seneca Falls and supporting Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s

controversial call for suffrage. Douglass later wrote, “The benefits accruing

from this movement for the equal rights of woman are not confined or limited to

woman only. They will be shared by every effort to promote the progress and

welfare of mankind everywhere and in all ages.”

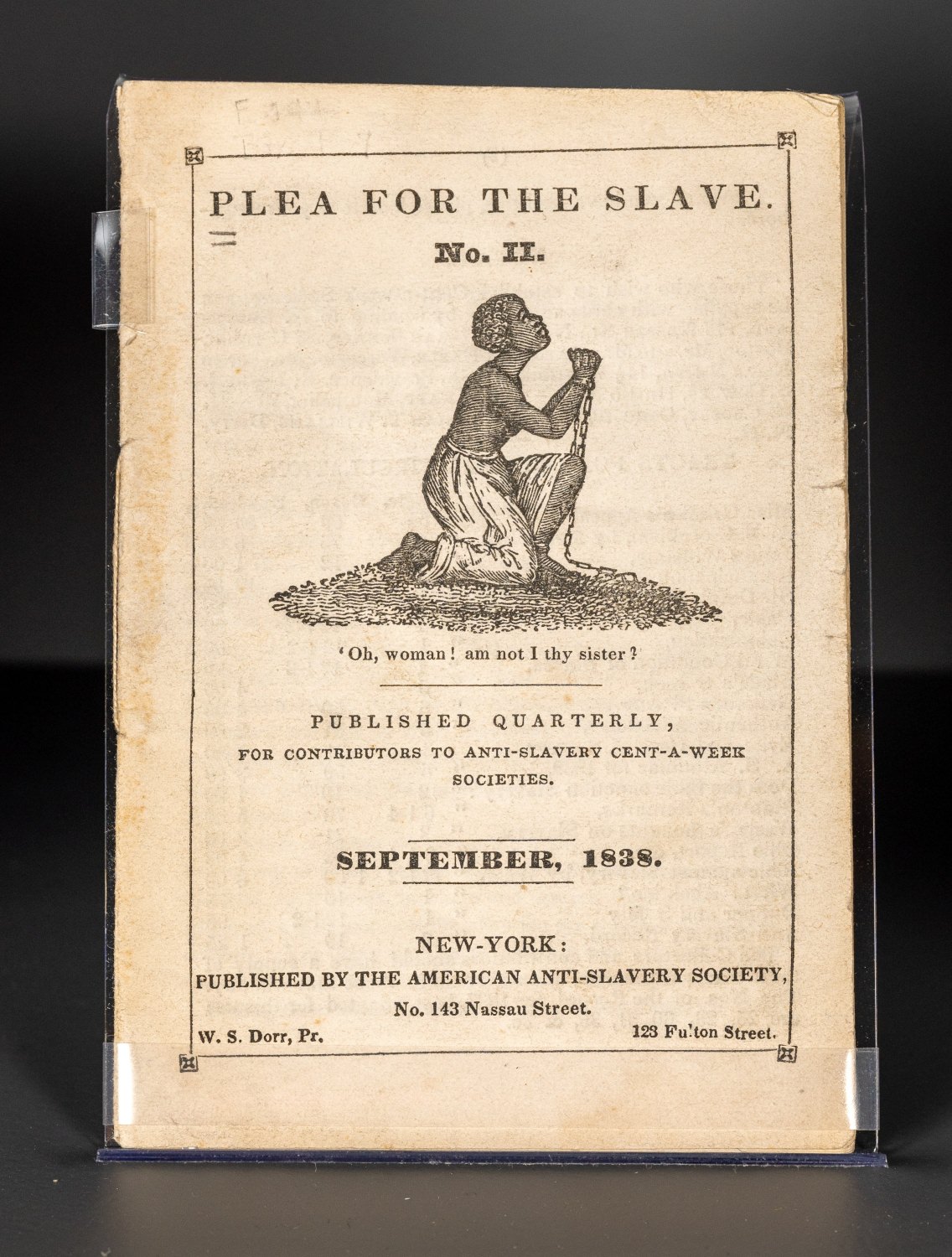

William

Doerr, printer

Plea for the Slave II

New York: The American

Anti-Slavery Society, 1838

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library,

New-York Historical Society

In 1824, an Englishwoman named Elizabeth Heyrick

published an influential pamphlet calling for the immediate, rather than

gradual, abolition of slavery. When the American Anti-Slavery Society was

founded in 1833, this still-radical call for immediate emancipation was

incorporated into its constitution. By 1840, the organization had 2000 auxiliary

societies, over 150,000 members, and distributed over three million pieces of

literature.

Hannah

Townsend and Mary Townsend

The Anti-Slavery Alphabet

Philadelphia: Printed for the

Anti-Slavery Fair, 1847

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library,

New-York Historical Society

Attributed to two Quaker sisters, this alphabet

book was printed for sale at the 1847 Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Fair.

The

authors concluded with a poem addressed “To Our Little Readers,” calling on

children to boycott sugar and sweets produced by enslaved laborers.

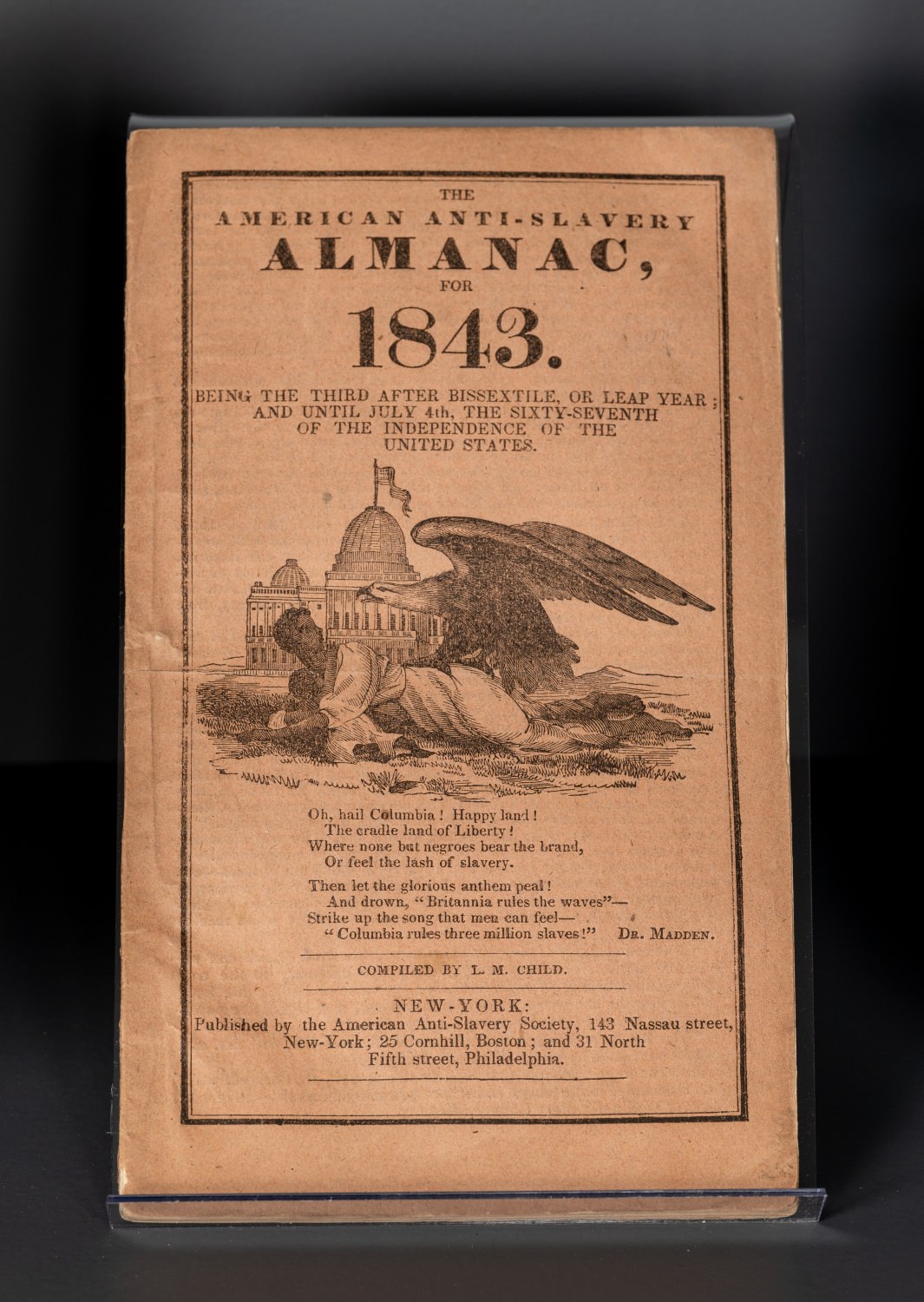

Lydia M. Child, editor

The American Anti-Slavery Almanac

for 1843

New York: The American

Anti-Slavery Society, 1842

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library,

New-York Historical Society

Lydia Maria Child was both a bestselling author and

an outspoken abolitionist. Like William Lloyd Garrison, Child advocated for

immediate and uncompensated emancipation. She also presented a forceful

argument against colonization - a proposal that all free Black Americans should

be sent to western Africa, regardless of their birthplace.

Olive Gilbert

Narrative of Sojourner Truth

Boston: Printed for the author, 1850

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

A young woman born into slavery in New York around 1797 was given the name Isabella;

however, in 1843, having escaped from slavery and undergone a powerful religious

experience, she claimed the name Sojourner Truth. Although she never learned to read or

write, Truth became a riveting public speaker. She supported herself by lecturing on

abolitionism and women’s rights, and selling copies of her autobiography, dictated to Olive

Gilbert.

“Her character becomes unnatural”

-The Pastoral Letter of the General Association of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts

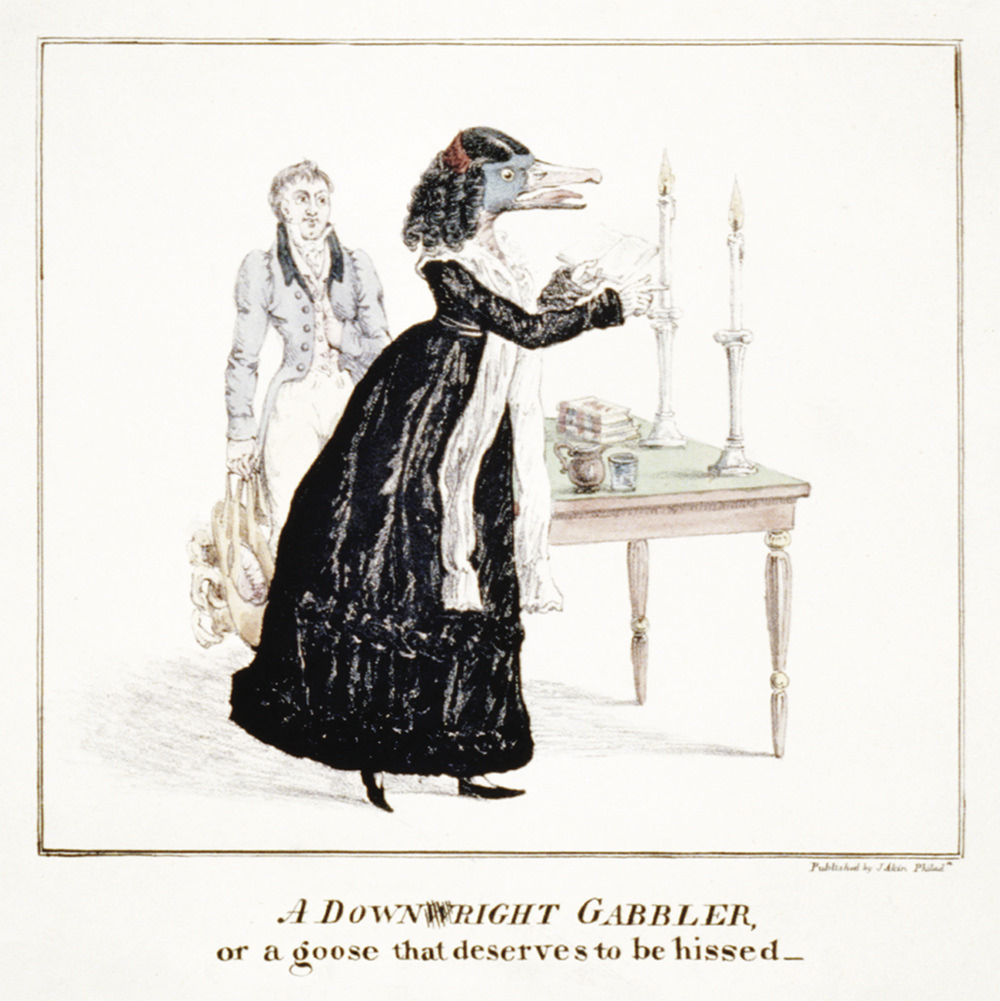

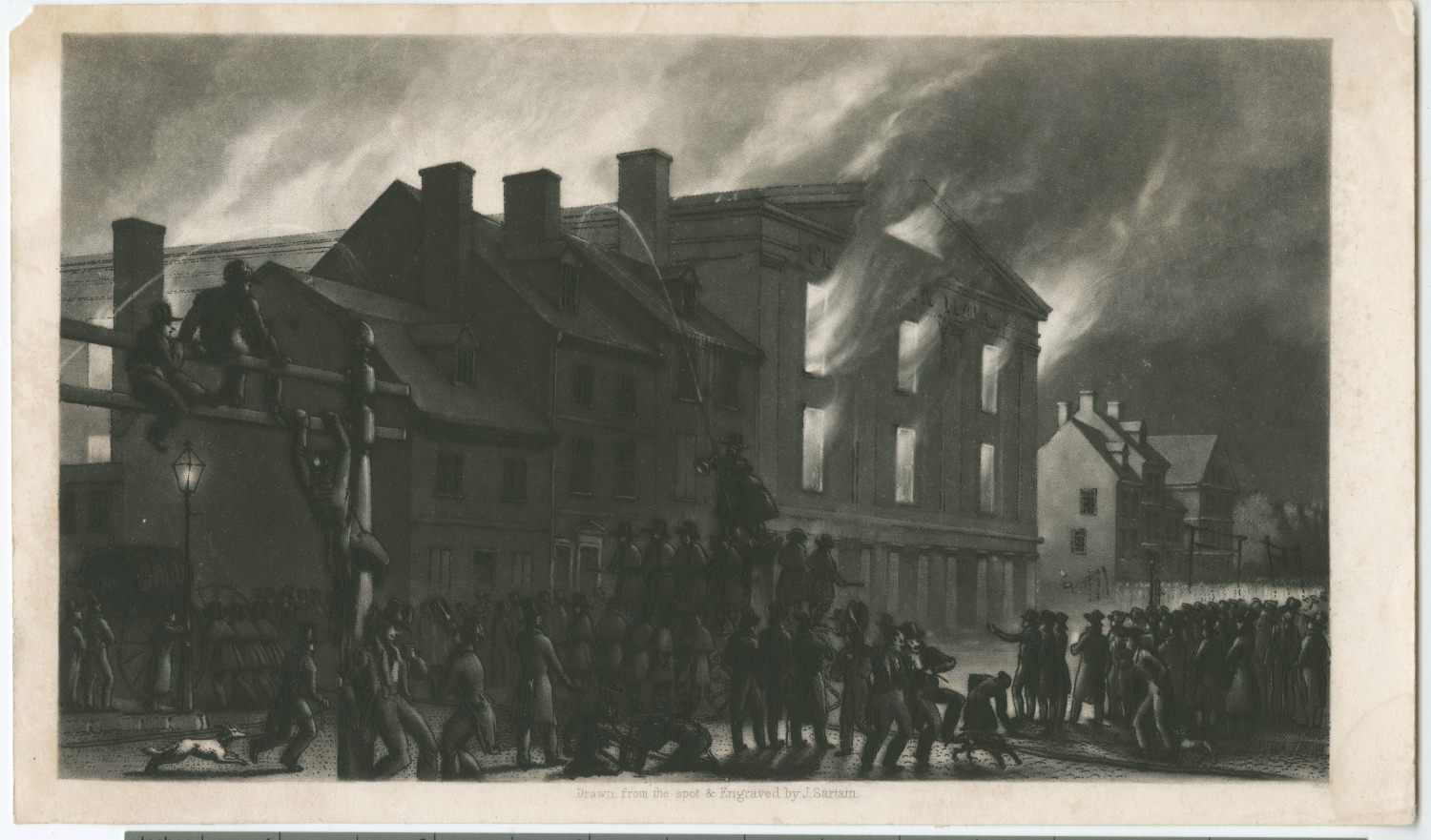

Women often encountered vicious condemnation for stepping outside their socially prescribed roles as wives, mothers, and homemakers. In 1828, when Scottish-born abolitionist and reformer Fanny Wright began giving public lectures, she was called “a great Red Harlot” and mockingly compared to a goose. Maria W. Stewart gave up public speaking in 1833, saying “I have made myself contemptible in the eyes of many, that I might win some. But it has been like labor in vain.” Taunts escalated into violence after the 1830s with over 150 incidents of white rioters targeting African American and white abolitionists. The unprecedented 1838 stoning and burning of Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hall was a response to Abby Kelley and Angelina Grimké Weld’s public orations before a “mixed” audience of men and women, Black and white, at the Second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, in the building the rioters called “Abolition Hall.”

James Akin

A Downwright Gabbler, or a goose that deserves to be hissed,

1829

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

John Sartain

Destruction

of Pennsylvania Hall, 1838

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

“Absolutely in the power of

her husband”

-Sarah Grimké

Women’s financial contributions were critical to the abolitionist movement. Yet their inequality under the law complicated fundraising efforts. Because married women were subject to coverture, a condition carried over from British colonial rule that gave husbands total control over their wives’ bodies, earnings, and property, not all American women could rely on ready access to cash. Some abolitionist accounts record women donating their rings instead, placing them in offering plates. In 1839, Mississippi became the first state to protect property that women brought into marriage: primarily, assets in enslaved African Americans. New York’s more expansive 1848 law safeguarded married women’s property, gifts, and bequests. Without such ownership rights, women were economically dependent and considered incapable of citizenship. Later that year, at the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY, Elizabeth Cady Stanton recognized the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act as an important first step towards equality for women.

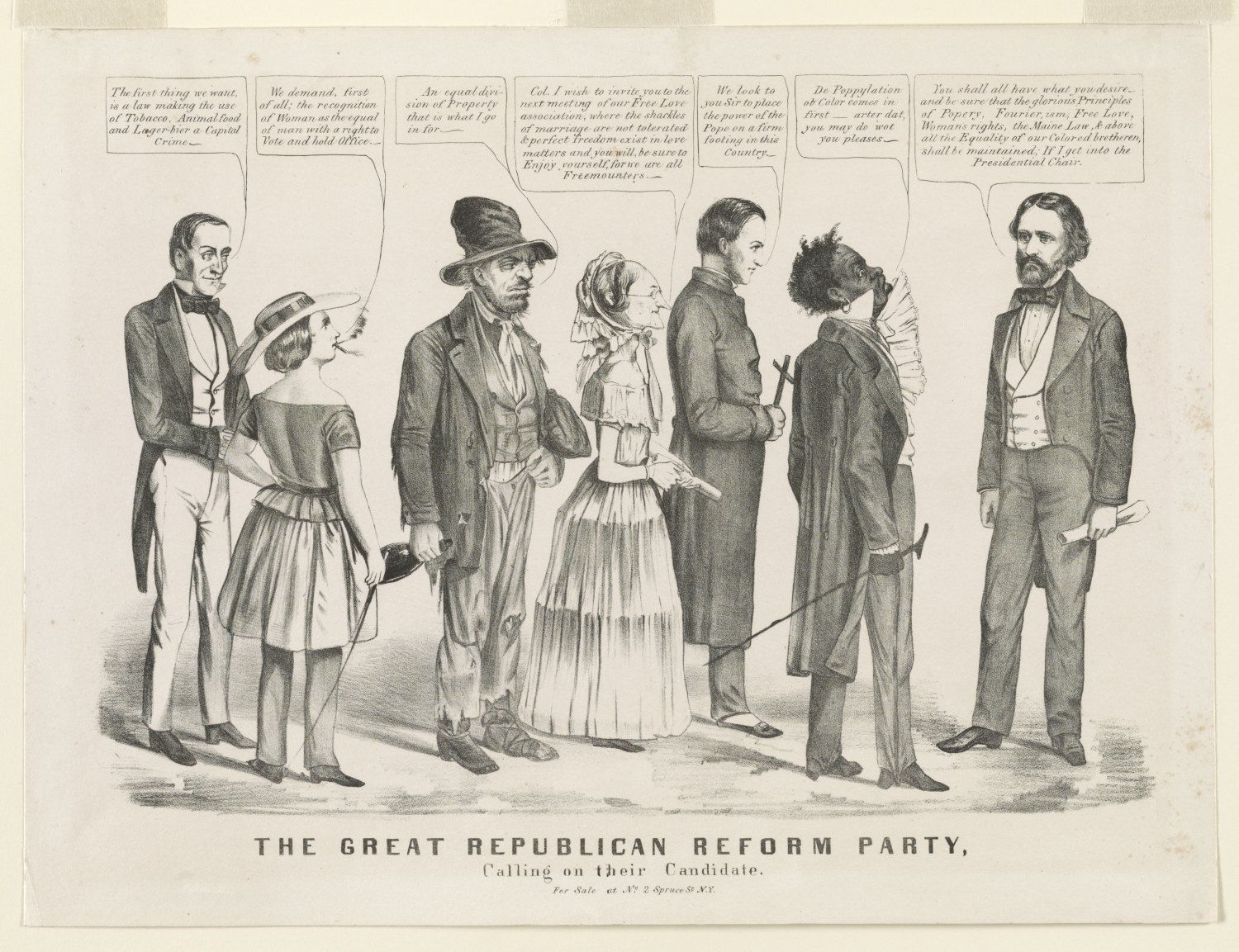

Attributed to Louis Maurer

The

Great Republican Reform Party

New York: Nathaniel Currier, 1856

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Although

some abolitionists refused to engage in politics, by the mid-1850s anti-slavery

and women’s rights activism led a growing number of women to partisan

positions. At the seventh National Woman’s Rights Convention in New York City,

Ernestine Rose argued that the fledgling Republican Party should support

suffrage, having courted women’s contributions during the 1856 presidential

election. Opponents mocked the suffragists as cigar-smoking, pants-wearing

extremists, lobbying the Republican candidate, John Frémont, alongside

caricatured advocates for temperance, free love, and racial equality.

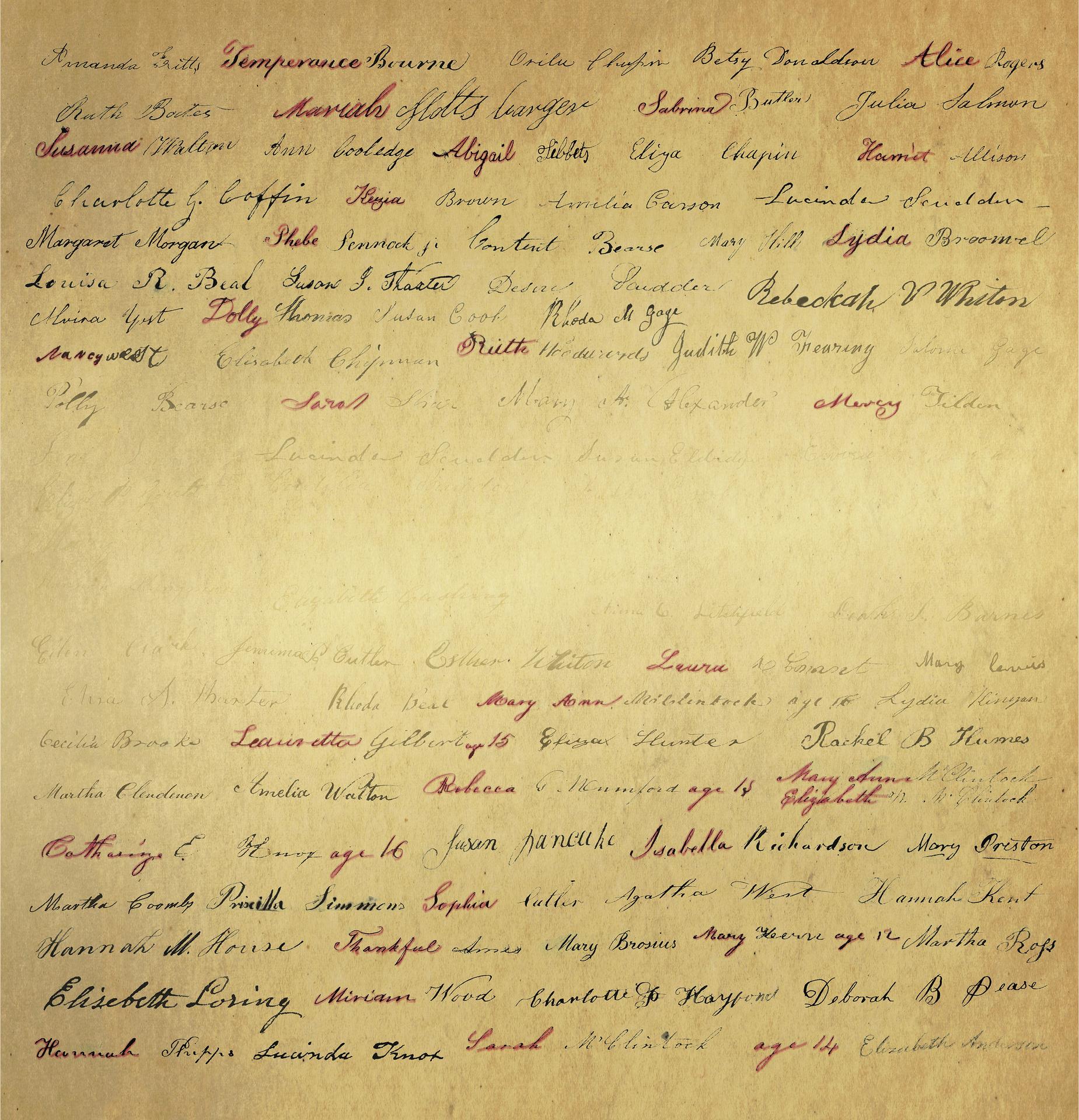

Petitions, 1835-38

Records of the 24th and 25th

Congress, National Archives

“The investigation of the rights of

the slave has led me to a better understanding of my own.”

- Angelina Grimké

Beginning in 1830, hundreds of thousands of women sought to influence national policy by petitioning Congress. Their signatures represented moral opposition to a number of pro-slavery policies: the Indian Removal Act, Texas annexation, the interstate slave trade, slavery in the District of Columbia, the Fugitive Slave Act, and the admission of slave states into the Union. The limited effectiveness of such moral appeals became clear in 1836, when the House of Representatives implemented a “gag rule” that automatically tabled all anti-slavery petitions without a hearing. This infuriated women who saw their First Amendment right to petition the government disregarded, intertwining abolitionism and women’s rights ever more closely. In her 1837 book Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, Sarah Grimké observed how, lacking political representation, “[woman] is only counted, like the slaves of the South, to swell the number of law-makers who form decrees for her government, with little reference to her benefit.”

Unidentified artist

“Have

Mercy Upon Us Miserable Sinners,”

Harper’s

Weekly

, October 31, 1857

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

Unidentified maker

Ring, 19th century

Gold

Bequest of Mary E. Warner,

1948.12

Unidentified maker

Ring, 19th century

Gold

Gift of Isabella Vaché Cox, INV.12373

Unidentified maker

Ring, 19th century

Gold

New-York Historical Society,

INV.769p

Unidentified maker

Ring, 19th century

Gold

New-York Historical Society,

INV.769q

Unidentified maker

Ring, 19th century

Gold

New-York Historical Society, INV.12371

“In her hands lie the destinies

of the

Republic”

- James Spalding

In 1837, 71 delegates attended the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, to coordinate nationwide activities. Angelina Grimké’s pamphlet, An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, emerged from this landmark event. Citing women’s Revolutionary-era boycott of British goods, Grimké called on Northern women to reject the products of slave labor. Meanwhile, some prominent activists, including William Lloyd Garrison, called for women’s equal participation in the American Anti-Slavery Society, the nation’s largest abolitionist organization. In 1840, four white women—Abby Kelley, Maria Chapman, Lydia M. Child, and Lucretia Mott—were elected officers, and the organization split. (Hester Lane, an African American woman, was nominated but not elected.) When the World Anti-Slavery Convention convened later in London, women delegates were not seated. Afterward, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton resolved to organize a national meeting advocating women’s rights—the seed of the 1848 convention in Seneca Falls. By 1860, ten national conventions on women's rights would be held in Massachusetts, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.

“Too strong to be satisfied with

a dress, a

pudding, or a beau.”

-Ellen Munroe

Beginning in the mid-1820s, vast numbers of young unmarried women left home to work a variety of jobs in the nation’s growing cities and industries. Joined by an increasing population of immigrant women, many labored twelve hours a day (or more) in noisy, stuffy, and often dangerous conditions, while receiving less pay than their male counterparts. In Lowell, MA, a textile manufacturing center, unsuccessful “turn-outs,” or strikes, in 1834 and 1836 convinced the “factory girls” to organize. In 1845 the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature to enact a ten-hour workday, leading to the first-ever state investigation of labor conditions. When the legislators refused to intervene, the LFLRA accused the Committee on Manufactures of “cringing servility to corporate monopolies.” The women campaigned against Committee Chairman William Schouler, calling him “unworthy of a seat in the halls of legislation” and contributing to his electoral defeat.

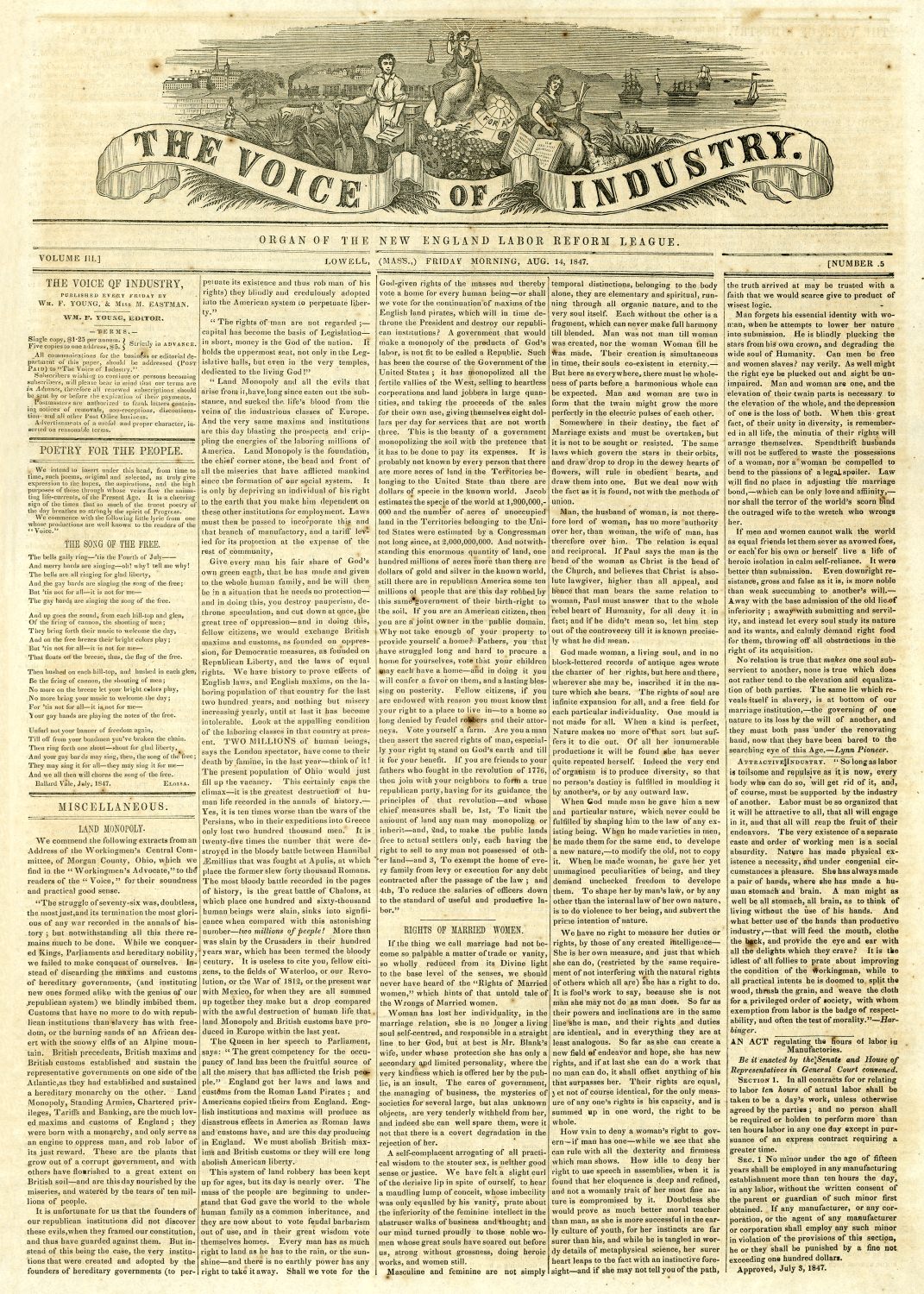

The Voice of Industry,

August 14,

1847

Wisconsin

Historical Society Library

The Lowell Female Labor Reform Association provided

key financial support for The Voice of

Industry, a regional newspaper. Sarah Bagley, then President of the LFLRA,

joined the Voice Publishing Committee

in 1845, and the weekly became a vocal advocate for equal pay and married

women’s rights. Ten years later, Massachusetts became one of the first states to pass a law protecting

married women’s wages, which had previously been her husband’s property.